From Blasphemy to Hate Speech (II. The Old Paradigm)

(Note: this essay is part of a series.)

The history of England’s “blasphemous libel” offence is roughly as one would expect. The document I read is The Evolution of the Law of Blasphemy (1922) by Courtney Kenny.

Prior to the Interregnum, blasphemous deeds were dealt with by the Courts Spiritual. In terms of British legal history, that was “the before time”, a very different situation that is of limited relevance to us now. After the Restoration, such deeds at first went unpunished, because the secular courts had no law with which to declare them crimes. These courts operated under both “statute law” (created by acts of Parliament) and “common law”. The latter was adapted by judges over time, and still is today. Each new legal precedent builds upon previous ones, modifying established norms as the times change. In this way, the fabric of English law evolves while remaining consistent and, for the most part, extremely well-tested.

The first conviction for blasphemy occurred in 1676:

A man named Taylor had uttered orally many highly offensive words against religion, words so wildly violent as to suggest doubts of his sanity.

Indeed, this was not respectful or decent denial of the Christian faith, but extreme verbiage that would be shocking to ordinary people. Leonard Levy quotes Taylor as saying:

Christ is a whore-master, and religion is a cheat, and profession is a cloak, and they are both cheats, and all the earth is mine, and I am a king’s son, my father sent me hither, and made me a fishermen to take vipers and I neither fear God, devil, nor man, for I am a younger brother to Christ, an angel of God and no man fears God but an hypocrite, Christ is a bastard, God damn and confound all your Gods, Christ is the whore’s master.

I think nowadays a man speaking like this would be given over to social services, probably sectioned. In 1676, there was only the judiciary to deal with such things. The matter was brought to court.

Sir Matthew Hale, who presided, emphatically asserted the jurisdiction of the secular Courts; saying “Contumelious reproaches of God or of the religion established are punishable here... The Christian religion is a part of the law itself… Such kind” - observe the limitation - “of wicked blasphemies are... a crime against the laws, State, and government, and therefore punishable in this Court... Christianity is parcel of the laws of England.”

Thus was the common law offence of blasphemous libel created.

As Kenny points out with “observe the limitation”, it did not criminalise any and all denial of Christianity, only “such kind of wicked blasphemies” as were uttered by a man so wild in his speech that some doubted he was sane. So, initially, the law was quite lenient and its bar for criminality high.

A much more stringent measure was introduced by Parliament with the Blasphemy Act 1697…

which made it a criminal offence (1) to maintain, either in writing or in advised speaking, that there are more Gods than one, or (2) to deny, in similar manner, the doctrine of the Trinity or the truth of the Christian religion, or the divine authority of the Scriptures

… but it was very rarely invoked, and no prosecution was ever actually made with it (it was abolished in 1967). Instead, the common law offence established 21 years earlier remained the legal instrument normally used against religious outrages.

In 1729, the offence was broadened to include any denial of the fundamental truth of Christianity. But this lasted much less than a century. In 1813, Thomas Starkie wrote of current usage:

The law visits not the honest errors, but the malice of mankind. A wilful intention to pervert, insult, and mislead others, by means of licentious and contumelious abuse applied to sacred subjects, or by wilful misrepresentations or wilful sophistry, calculated to mislead the ignorant and unwary, is the criterion and test of guilt. A malicious and mischievous intention, or what is equivalent to such an intention, in law, as well as morals – a state of apathy and indifference to the interests of society – is the broad boundary between right and wrong.

In 1841 the Commissioners on Criminal Law reported:

The law distinctly forbids all denial of the Christian religion [but in practice] the course has been to withhold the application of the penal law unless insulting language is used.

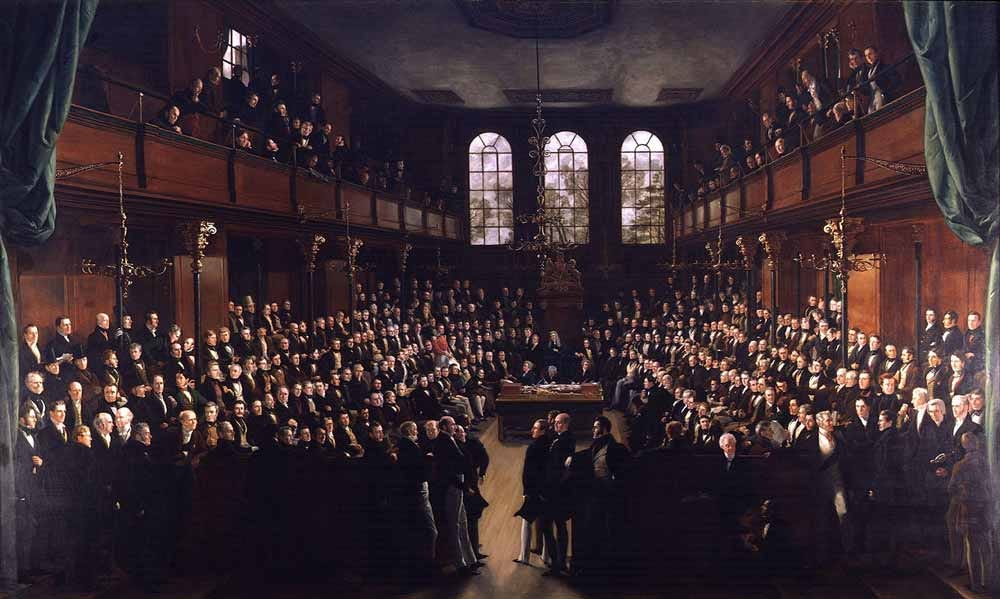

In 1833, Lord Macaulay spoke in Parliament advocating reform, outraged not at the practice of the law but at its formal definition:

It is monstrous to see any Judge try a man for blasphemy under the present law. Every man ought to be at liberty to discuss the evidences of religion.

However, having affirmed freedom of speech, he affirmed the need for the law’s protections:

but no man ought to be at liberty to force on the unwilling ears and eyes of others sounds and sights which must cause annoyance and irritation. The distinction is clear. I think it wrong to punish a man for selling Paine’s Age of Reason in a back shop to those who choose to buy... But… if a man in a place of public resort applies opprobrious epithets to names held in reverence by all Christians; such a man ought, in my opinion, to be severely punished, not for differing from us in opinion, but for committing a nuisance which gives us pain and disgust.

Two years later Macaulay drafted India’s Penal Code. True to his word, he included this offence:

Whoever, with the deliberate intention of wounding the religious feelings of any person, utters any word or makes any sound in the hearing of that person or makes any gesture in the sight of that person, or places any object in the sight of that person, shall be punished with imprisonment... for a term which may extend to one year, or with fine or with both.

Returning to his 1833 speech, he interestingly (for a Whig) understood that such rules cannot be universalised; they must be tailored for a people and place:

I am not a Roman Catholic; but if I were a judge at Malta, I should have no scruple about punishing a bigoted Protestant who should burn the Pope in effigy before the eyes of thousands of Roman Catholics. I am not a Mussulman; but if I were a judge in India, I should have no scruple about punishing a Christian who should pollute a mosque.

If I understand correctly, he was saying that the proper course is not absolute freedom of speech, nor the opposite extreme of forbidding blasphemy against any and all religions, but forbidding it against the religion(s) of the place. (This point will be crucial later on.) In England for example, it made sense to forbid blasphemy against Christianity so as to protect the majority, but not against Islam since the vast majority of Britons were not Muslim and, furthermore, Islam was positively alien to them and their culture.

After 1857, 25 years passed without any prosecutions for the offence. Then in 1882 there was a surprise development.

George William Foote, a committed Secularist and republican, edited “a weekly paper containing hideously offensive caricatures - literary and pictorial - of religion”. He was convicted twice and eventually spent a year in prison.

Foote would write in 1886:

I was also preparing the second Christmas Number of the Freethinker. The announcement of its contents caused a great deal of excitement, and I am prepared to admit that it was, to use a common phrase, the “warmest” publication ever issued. It was full from cover to cover of what the orthodox call blasphemy, and it was speedily described by the Christian press as more “outrageous” than any of the ordinary numbers for which we were already prosecuted. The description was perfectly correct. I had concluded that my wisest policy, as it was certainly the most courageous, was to disregard the Blasphemy Laws and defy the bigots; to show that Freethought was not to be cowed or intimidated by threats of imprisonment. Facing the enemy boldly appeared to me better than running away; a course in which I could see neither glory, honour, nor profit... I have paid the full penalty of my policy; I have suffered twelve months’ torture in a Christian gaol; yet I do not repent the course I took; and ever since my release from prison I have felt it my duty to continue doing the very thing for which I was punished.

Note how, as the type I described in part 1, he positively revels in the upset he has caused people. Having antagonised and received the predictable (and desired) response, his reaction is not to wise up and stop antagonising, but to be outraged by the response he provoked and antagonise more. His rights (as he sees them) have been violated, so he will go to war with his entire society and aim to topple the pillars it most relies upon. Other people (whom he will despise) can worry about the resulting chaos; his only concern is his ego. Worst of all, he will justify this arrogance (to others and to himself) by saying that he is concerned with “the truth”.

I don’t believe for a second that this man was actually opposed to Christianity in and of itself. Rather, I believe he was opposed to his fellow man, to ordinary people, to the stability of his society, and to the very concept of bourgeois decency. In that quote, the idea that he has a responsibility not to unduly upset the general public - his community - is alien to him. He is proud of the harm he has done and is determined to do more.

Note also that his overriding interest is his own persecution. This shows self-absorption and exhibitionism - two traits common among people who deliberately offend the sensibilities of their time in order to become persecuted. To “justify” this drive for glorious martyrdom, Foote equates courage with wisdom - as if a fool cannot be courageous in his foolishness!

Judging by this and other passages in that document, George Foote was a grandiose, vain, self-obsessed and malicious destroyer. To save society from his malign influence, I would cheerfully have imprisoned him for life. I believe it was decadent late Victorian naivety to spare him this fate he deserved.

However, many of the working-class felt differently. Kenny tells the story:

The conviction [of Foote] aroused much feeling among the working classes; and at the general election of 1885 “the repeal of the Blasphemy Laws” was strongly urged upon all candidates for working-class constituencies.

Kenny himself was a candidate in that election and got voted in. He then became the first man ever to attempt abolition. But he was no destroyer. Like Lord Macaulay and myself, he believed that, while denials of Christianity should be allowed, the blasphemy offence did serve the useful function of protecting public feeling. If one was to abolish the offence, it was right to recreate that protection with a new law.

On my entering Parliament in that year, Mr. Bradlaugh, then the leader of the Secularist party, asked me to introduce a Bill for that purpose, which I accordingly did. This “Religious Prosecutions Abolition Bill” proposed to do away with both the common and the statute law against blasphemy; but to replace them - as I felt to be essential - by the enactment of Macaulay’s prohibition against intentional insults to religious feeling.

But the Secularists, who had asked for this bill, did not share his concern for public feeling.

The general body of Secularists at large refused to accept anything but an unqualified and absolute licence in controversy. Mr. Bradlaugh accordingly… said that he must oppose the Bill if it were carried to a second reading. It accordingly dropped. But when he in 1889 re-introduced it without Macaulay’s protecting clause, the absence of that limitation was made so strong an objection to the measure that the second reading was negatived by 111 votes against 46.

So the Secularists threw away two chances to get the offence abolished because they would not accept a new law against “intentional insults to religious feeling”. They demanded nothing less than “absolute license in controversy”. Clearly, they did not understand the efficacy of demanding change in polite increments, something well known to the nihilists who succeeded them (and succeeded).

Thus, the offence survived into the 20th Century.

A good summary of the offence’s history between 1900 and 1976 is given by New Humanist magazine:

There were many prosecutions during the early years of the twentieth century - in 1908, 1909, 1911 (twice), 1912 (four times), 1913, 1916, 1917 (twice), and 1921 (twice)…

After this string of convictions, it stopped abruptly. That final conviction in 1921 led to a sentence of hard labour for the accused which probably caused his early death soon after release; perhaps this weakened the judiciary’s appetite for future convictions for the offence.

This, 1922, is when Kenny wrote his essay. I was quite amazed to find this paragraph towards the end of it:

[The offence is] a wise rule. But a rule which, it seems to me, needs to be universalized by Parliamentary legislation. Christianity is thus protected against wanton insult. But the rule falls far short of Macaulay’s Indian clause, which protected every man against an insult to the religion dear to him. On the prosecution in 1838 of a clergyman named Gathercole, for a libel on the nuns of a convent in Yorkshire, it was laid down… that “If this is only a libel on the whole Roman Catholic Church generally, the defendant is entitled to be acquitted. A person may, without being liable to prosecution for it, attack Judaism or Mahometanism; or even any sect of the Christian religion, save the established religion of the country.” … But, not to speak of the rights of dissenting Christian sects or of the Jews, the presence in England to-day of many followers of Muhammad and of Buddha suggests the importance of an extension, even to those faiths, of the protection - what is now the moderate and just protection - which the law gives to Christianity.

This criticism of the offence - that it is not multi-religion - would later become ubiquitous and the main reason (I would say excuse) for abolition, but Kenny’s 1922 essay is the earliest voicing of it that I have found. It seems unlikely to me that he originated it; he seems to be voicing a sentiment fairly widespread in his (liberal) circles. However, the next voicing of it I have found is from 55 years later - perhaps only because the offence fell out of use until then.

Before we move forwards, it is worth making some points about Kenny’s recommendation. It is possible that Macaulay defined the Indian offence as universal for ideological (Whig) reasons, but given that he seemed to understand the importance of time and place to the shaping of law, it seems more likely to me that he did it because he knew how chaotically multi-religious India was at that time (and still is). It would simply be the safest option to include any and all religions, and, given the reality of India, probably the wisest option.

But the caveat is that those many religions present in India had been present there for centuries (Islam having “arrived” in 1526) and millennia. The situation in England, even today let alone in 1922, is very different. Also, for Kenny to speak of “many followers of Muhammad and of Buddha” seems laughable now. In truth, they were present in such minuscule numbers that they could expect, and I would say were entitled to, no special accommodation whatsoever in English law.

I think Kenny and his associates must have been very much “out on a limb” with this point. Even decades later, the common opinion among the intelligentsia was still that England was a Christian country - overwhelmingly in numbers, and profoundly in character.

In 1949, something occurred which gives a flavour of the mood regarding the blasphemous libel offence: Lord Denning declared it obsolete. Ever since, his words have been used frequently by people defending abolition. Here, for example, is the Guardian in 2008:

The ancient common law offence of blasphemy, Lord Denning once declared, was a “dead letter”. He explained how “a denial of Christianity” was once thought “liable to shake the fabric of society” but that such fears were no longer relevant.

The obvious interpretation here is that Lord Denning believed England had become broadly Atheistic, so a law against Christian blasphemy was now inappropriate. Christianity was no longer central to the fabric of society, therefore said fabric would not be shaken by blasphemy against it. However, to read Denning’s actual words is to find that his meaning was entirely different. In fact his thinking was diametrically opposed to that of the Secularists, Humanists and Guardian journalists who have quoted him.