(Note: this essay is part of a series.)

One might assume that the main objection the British Establishment had to the blasphemous libel offence was that it pertained to religion, when the Establishment increasingly held religion in contempt. I dare say this is correct, however, the main objection voiced was that the offence pertained only to Christianity and was therefore unfit for a multicultural society.

The concern was raised by Courtney Kenny in 1922, by John Mortimer QC in the 1977 Gay News trial, by the British Humanist Association, by the Lords in their 1978 debate, by the Law Commission in their 1981 working paper and their 1985 report, and by countless Guardian journalists.

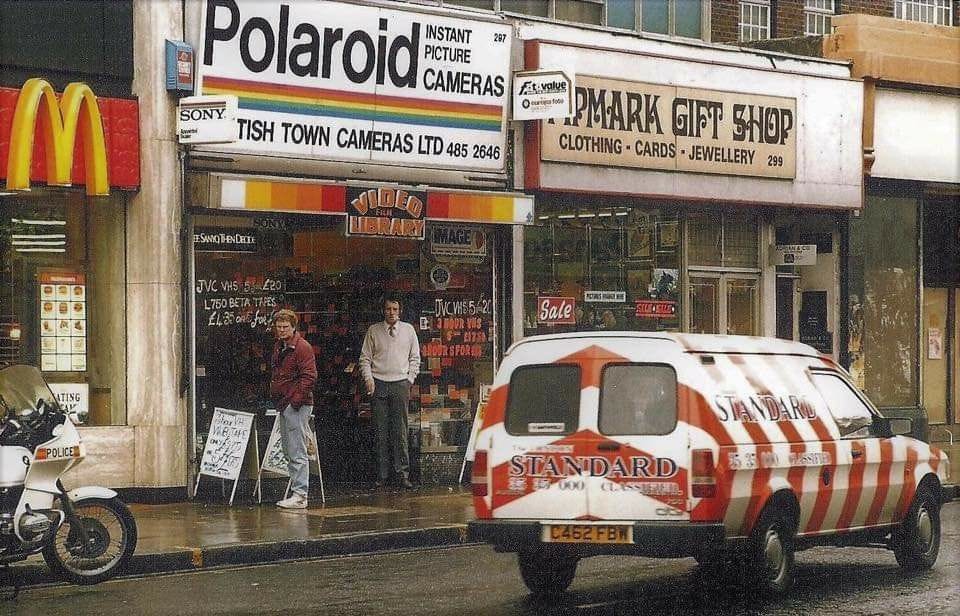

I find it surprising that so many people had this objection as long ago as the 1970s, when Britain was barely multicultural at all compared with today. Perhaps, for Mortimer, it was just an argument he gleaned from Kenny and thought worth trying in defending his client, but then the Establishment realised how useful it was and took it up.

It is clear why it was so useful for an Establishment seeking to remodel the country (as ours certainly was). A law which only protects Christianity is not merely “not multicultural”, it is “counter multicultural”. It is therefore an obstacle, in spirit if not in practice, to multiculturalising the country. Perhaps more than any other law in England, this one stipulated the character of England. It implicitly told foreigners:

In England, one particular religion has a special place. That means England has a particular character which predates your arrival and is not shaken by your presence here. England is not just an economic zone or a set of rules. It is a homeland, and you are an outsider. You must respect, not try to change or defeat, our national character. Christianity might mean nothing to you or even be historically offensive to you, but if you insult it in England, you will be punished by England.

Not exactly a welcoming or open-minded message.

Endorsing Christianity in this way alienates foreigners - and reminds them that they are foreigners - but it also signals to the natives what their society is “all about”, thus giving them something to hold on to. That might be just as undesirable for an Establishment which was, by this time, bent on betraying the natives.

There are four options:

keep things as they are. Any foreigners who feel alienated by the blasphemy offence just have to “deal with it”

expand the offence to cover other religions

abolish the offence

deport the foreigners who feel alienated by it

In the Gay News trial, Judge King-Hamilton advocated solution #2:

I would be prepared to extend the definition to cover similar attacks on some other religion, as we have now become a multi-religion state, but it is not necessary for me to go so far for the purpose of the present case.

Presumably he imagined that the next judge presiding over a blasphemy trial, if it pertained to some other religion, would extend the definition.

An anonymous letter-writer wrote to the Times.

He believed King-Hamilton was mistaken:

King-Hamilton seems to have been wrong in stating that the ambit of the offence was wide enough to encompass offensive aspersions on other religions. There is authority to the effect that it is not blasphemy to vilify the Jewish or any other non-Christian religion.

(The letter-writer turned out to be correct, as we will see later.)

It may not have mattered too much until recently that the offence was so narrowly defined. Today, however, substantial minorities of British citizens follow religions other than Christianity, and, indeed, a high proportion of them are devout followers, who would perhaps take even greater exception to derogatorily offensive remarks about their gods than would most Christians to similar language about Christ.

Looking back from 2024, “substantial minorities” is an absurd exaggeration for 1977. However, he is prescient in saying that some of these newcomers to Britain, namely Muslims, would “take even greater exception” to blasphemy against their religion than would docile Christians. Theo van Gogh, the staff of Charlie Hebdo, and Salman Rushdie himself demonstrate that.

If blasphemy is to remain a crime, adherents of the main non-Christian religions should also be entitled to have the benefit of its protection. Where to draw the line could cause difficulties. Muslims, Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists and Jews would clearly need to be placed on the same footing as Christians.

Placing those religions “on the same footing” as Christianity would, in itself, radically change the nature of Britain. I don’t think people like this letter-writer understood the repercussions of their proposal; in 1977 it was all theoretical and abstract. The paucity of diversity back then probably made them think English culture was invincible, and a fundamental change would have no fundamental effects “on the ground” but would merely create that consistency by which the Anglo mind is so enthralled.

This change would:

disenfranchise the native (Christian/post-Christian) majority

embolden the minorities against that majority

pave the way for one of those minorities to eventually take over the country, by formally casting their presence here as legitimate and removing the natives’ ability to see them as “visitors”

Leaving all of that aside, there is a more immediate problem: how to persuade the natives that this situation is right and just? By asking John Bull to respect some religion he knows nothing about, you are telling him his country is no longer familiar, no longer predictable and no longer his. That in turn makes him question - rightly - what his country exists for. And then why should he defend it?

For the letter-writer, such psychological and social effects are but an imperceptible cloud on the horizon. He is concerned only with dilemmas of implementation:

But what of the innumerable minor sects and quasi-religions which have a presence in Britain? The protection should be confined to major religions and not be extended to the scientologists or Mr Moon.

Indeed, which religions to include and which to exclude? This is lethal. What the letter-writer doesn’t understand, because he is not inured to diversity, is that you actually can’t do what he is suggesting. In a context of diversity, to exclude any religion from any provision is to condemn it as second-class - and that’s discrimination.

The pre-Blair House of Lords was always described as full of crusty conservative bigots, but even during the 1978 debate in there, one speaker after another is at pains to emphasise that he understands Britain is now multicultural. Most of them argue for solution #2 from above, other religions becoming in future similarly protected as Christianity (then) was.

One example is Lord Ferrier. Though his heart is clearly in the right place, he is woefully naive:

I have spent much of my life in the East and have associated on a very friendly and intimate basis with many Hindus and Moslems and came out by that same door wherein I went. I agree with… Lord Gardiner, that our laws should protect other faiths from this sin, I think, of blasphemy.

This comes from the same place as “I know a nice black guy, therefore let’s import millions of them”. It is also similarly unworkable in practice. For a nation to protect all faiths from mockery is for it to no longer be a homeland, but a generic system for human livestock.

I can understand his sentiment that to blaspheme is to sin, but can that really work in the real world? I believe law is tied to a place, which is tied to a people. Things are justifiable in defence of that people which are not justifiable in defence of an abstract principle. To blaspheme against another man’s religion is impolite, even unseemly, but… sinful? This is the creed of the pathologically tolerant and welcoming, the creed of men who have forgotten that they need to lay claim to what is theirs otherwise it soon won’t be. It is not so much that “might makes right”, as “mine makes right”. This might seem barbaric and, to the Anglo mind, disgustingly inconsistent, but in the end it is the only attitude that prepares one for a real world in which other men will, if they can, if one allows it, steal what one owns, desecrate what one holds sacred, and attack what one should be protecting. The law of the jungle holds true in the affairs of even civilised men - but especially when they have imported the jungle.

There are many other speakers in that House of Lords debate saying versions of the same thing. They want the blasphemy offence retained, but expanded. That is the only way they can justify retaining it. Not a single one of them has the courage to say what the vast majority of the public would have said at the time: “this is a Christian country”.

In 1985 the Law Commission completed their long-running inquiry, publishing a report. They had several other objections to the blasphemy offence but, again, their main one was that it only protected Christianity. Their assumption, shared in 1977 by John Mortimer, was that Britain was no longer “a Christian country”.

That was certainly a lie. This was an Establishment group “finding” what they wanted to find, building one delusion upon another, when the truth was right in front of them if they chose to see it. Gallup polling leaves no doubt that Britain was overwhelmingly Christian at this time:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Millennial Woes to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.