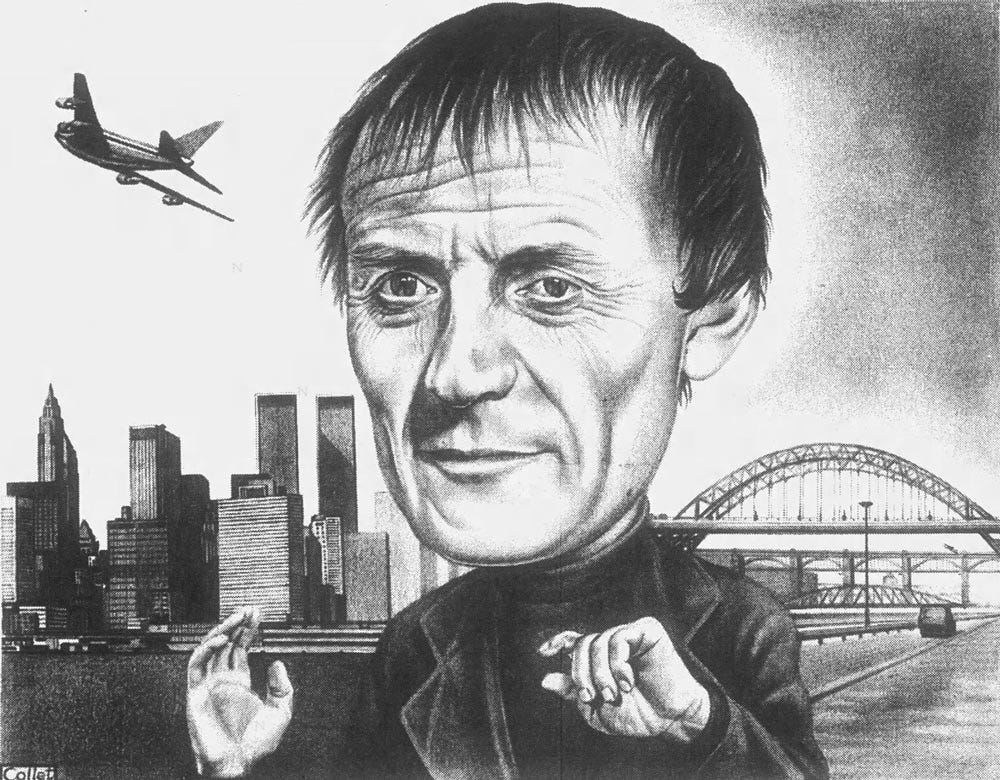

I have always greatly admired Tony Harrison (1937-), a vehemently working-class poet from Leeds. Harrison has unmistakable talent and, much rarer, moral integrity. His work avoids the lofty obscurantism of so much modern poetry. The subject and meaning are clear, and there is a total absence of pretentiousness. There is a vivid social conscience and wry observation of contradictions, ironies and uncomfortable truths. But he is not just “a political poet”; sometimes he is simply a witness, a dispassionate recorder of being human.

While producing work of great quality, Harrison is also an innovator. He pioneered the rare format of the “film-poem”. It was this blending of approaches - film and poetry - which excited me when I first discovered him in 1997 by way of a short TV documentary.

The two high points in his career are V (1987) and Prometheus (1998) but he made ten other film-poems which are more obscure but just as interesting. In this series I will be examining all that are available to me - some on YouTube, some at the BFI. (Sadly there is no DVD boxset of Harrison’s oeuvre. There really should be.) I will also examine several of his poems.

However, in finally writing about this man I have admired for 27 years, I will be voicing a lot of disagreement.

It is obviously true that every man is a product of his time, but also true is that each man has to operate within his time, and has to satisfy (to at least some extent) the axioms of his era. That is to say, we are both created and constrained by the times we grow up into. Of course this is much less true for people on the fringes like myself, but for an artist like Tony Harrison who pursued mainstream acceptance, the pressure to not see certain things, or to see them but forget them, or to see them but misinterpret them, would be very real.

There is also the matter of innocence, or naivety, or ignorance. Some things are simply not obvious - or, rather, they remain deniable - until they have played out. For example, I can forgive a lot of hopeful thinking about multiculturalism early on, because while the numbers were tiny it would have been easy to imagine that “we’ll find a way to rub along together”. Harrison would have felt this pressure quite acutely, since he was both from the “narrow-minded” working-class (and very aware of their mentality) and enmeshed in the “enlightened” upper-middle-class milieu of media and art.

He was also sponsored, in 1969, by UNESCO. I was surprised to learn this because I didn’t realise how far back this kind of thing went. By that I mean the reaching of globalist bodies into the culture-shaping parts of society - funding this, funding against that, in order to cultivate a certain new culture. Harrison’s pampering by UNESCO - a six-month “travelling scholarship” which took him around the world with his wife and their two small children - would have left him feeling not just welcomed into that higher echelon, but in some sense obligated to it.

To be clear, I do not mean that Harrison was compromised and spent the rest of his life kissing the feet of globalist paymasters. That would be both unfair and an absurd caricature. It would be a minuscule expense for UNESCO to send a small family around the world for six months, so I doubt Harrison thereafter felt any great need to say “what they want to hear”. Indeed, at times he said things that ideological globalists definitely wouldn’t want to hear - and we will examine several of those occasions in this series. But I do think it would be natural for him to feel that he had ascended to a better, more open-minded plane. With that mentality, the bigotry of the working-class would look like something to be “managed”, never acceded to, and their suffering something to be reduced in a way compatible with globalism, not oppositional to it.

Another relevant factor is the background of his first wife, the mother of his two children. Rosemarie Crossfield Dietzsch had come to England with her Czech parents, refugees from the Third Reich since her father was a Communist. I am unsure whether she was Jewish, but either way, being married (from the age of 23) to a former refugee would surely inform not only Harrison’s treatment of said regime, but the general worldview which manifests in his work.

The marriage, in 1960, happened “by default”; Rosemarie had fallen pregnant. In the event she had a miscarriage, but they loved each other so remained together, and soon had a daughter and a son. In the meantime, Harrison began an international career. He lectured for four years at a university in Nigeria, then for a year in Prague, then won the Northern Arts fellowship. For that, his family lived for two years in Newcastle.

That is why, when they were at the start of their 1969 travels, they were interviewed for the Newcastle Journal. They were in Nigeria at the time, a country they already knew well. The reporter, Maureen Knight, paints the family in a very idealistic light:

Jane [7] and Max [4] belong to the new wave of cosmopolitan kids, whose parents are travel conscious and internationally minded.

Rosemarie is quoted:

I would like to send Jane to school anywhere where we spend more than a month. I shall have to visit one or two schools to see what they do and if Jane will fit in. I can’t see any school in any country where a child would not fit in. I want her to have the company.

When they were living in Prague for a year, Jane attended the English-speaking international school. Rosemarie adds:

But after school she played with the local Czech children and quickly picked up their play phrases.

This would please Rosemarie not only for globo-political reasons. However, there is a much smaller difference between English and Czechs than between Europeans and black Africans. Just because a little English girl got along well with Czech children, it does not follow that she could ever “fit in” among black kids in Nigeria. Indeed, any realistic person knows that she would stick out like a sore thumb, and not just visually. But none of the grown-ups seem to be concerned about such uncomfortable truths. Instead, Knight describes a family very much “at one” with travelling, a family for whom the very idea of “home” seems to be irrelevant:

Abroad they have always lived in furnished accommodation. At home they have furnished from auctions and thrown away most of it when they left. Their treasured belongings are small things they have collected on their travels, a piece of material from Nigeria used as a wall hanging, a few African carvings and pictures and puppets from Czechoslovakia. It is not important that sugar is spooned from a pot marked “Cumberland Butter”.

Yet Harrison was, and remains, very attached to northern England, so the above is a mirage, or at best only half of the truth. I suspect this was as much the family’s own self-image, conveyed to Knight, as anything she came up with herself. I also suspect it was all a bit more innocent and well-intentioned than the oikophobic globalism of today.

Rosemarie:

We want to travel to cement friendships and find common ground with people of all nations.

Harrison himself is quoted:

People get their pensions and at 65 they set off to see the world. The older you are the less absorbent you are to new ideas. I feel you should be able to do it the other way round - draw one’s pension at 25 and pay it back.

This strikes me as something that could be said by any globalist apparatchik today - a subscription to the world, a debt you spend your entire life paying back. While you bask in the trivial novelties of never settling down, the powerful own you completely.

Harrison continued:

Travel can relax international tension and everyone can do it. It should be part of our educational system.

Knight remarks optimistically:

When that time comes, cosmopolitan kids like Jane and Max will be everywhere.

But the kids did not turn out all that cosmopolitan, in fact. Jane became an archaeologist, fascinated by the mysteries of the British landmass. The seeds of the cosmopolitan delusion are actually in the article itself, when Knight happens to mention that, for all their love of travel, they have in fact already put down roots:

This trip, however, they have realised it is better to forfeit £200 keeping up their charming rented house in the Grove at Gosforth, than to throw out and start again.

As far as I can tell, Harrison is still living in that house today, 55 years later. He was certainly still in Gosforth in 2013. Yes, he has done a lot of travelling in that time, but the idea of him being a rootless cosmopolitan who belongs nowhere and everywhere, is utterly untrue.

But the marriage to Rosemarie didn’t last forever. Ten years after that happy 1969 interview, bitterness and infidelity had poisoned things and they got divorced. In 1984 Harrison married Greco-Canadian opera singer Teresa Stratas. Within the decade that marriage too would take a back seat when he began an affair with the actress Siân Thomas. He seems to remain very close with both women to this day, though not Rosemarie.

So Harrison as he was in 1969 is, ironically, as conventional as he gets. He and Rosemarie loved each other and were raising two happy children in the best way they knew. But even then, he was exploring the world and germinating a career in poetry.

After Nigeria, the family’s UNESCO trip took them to Cuba, Brazil, Senegal and Gambia. Then they returned to Newcastle, and Harrison couldn’t find work and ended up on the dole. But that might have been the saving of him as an artist:

I like living in areas where the sense of being a poet is continually being put to question... it helps to prevent you falling into pretentiousness.

Very soon after, his first volume of poetry was published: The Loiners, a set of meditations on his Leeds childhood and his adulthood travels. He had been working on it for years and it immediately established his reputation.

From then, one thing quickly led to another. Within three years he had a play on at the Old Vic starring Diana Rigg. Soon, he was fielding job offers from Hollywood. But he turned virtually all of them down, because (I believe) he had a genuine commitment to artistic integrity.

In 1975, he would tell the Newcastle Journal:

Like others, I’m disappointed with some of the results of socialism in certain countries lately, but broadly speaking I am socialist. Having spent a deal of time in both the USA and the USSR, I know which side I prefer.

Bearing in mind that this man could easily have been very rich, I think it’s fair to say that he is no fraud, and no champagne socialist.

Also, his ideas about left-wing regimes were not rose-tinted. When living in Prague he went to the theatre every evening, and saw Communist censorship bearing down upon the arts. That same regime suppressed the work of his friend and fellow poet Miroslav Holub.

But still, his worldview is fundamentally of the Left, rejecting social hierarchy, cultural hierarchy, and the concept of God:

I prefer the idea of men speaking to men to a man speaking to a god, or even worse to Oxford’s anointed.

His socialist ideals are linked with - I won’t say caused by - resentment towards Britain’s class structure. This had hit an eleven year-old Harrison in the face. Coming from Beeston, Leeds, he was from a working-class family (his father was a baker) in which education levels were very low. One of his uncles was mute, another stammered. His parents were not readers and had no books, but they did not obstruct young Tony’s interest in reading. When neighbours offered them their old books for him, he received them.

But then, at eleven, he won a scholarship to the elite Leeds Grammar School. This created a divide between him and his family. He would become more educated than any of them, and this would make him a different kind of man. Class sensitivity was so acute in Britain at that time, it was a somewhat glaring contradiction for someone to be both working-class and educated; the two were not supposed to coincide, and, when they did, the individual would have problems and a rather stark choice to make.

In Harrison’s case, he resented being forced into that position. He still does. He has spent his life railing against the institution that tried to change him, and the Britain that authorised it to do so.

This was a problem experienced by many working-class boys of his generation, because there was a proliferation of state grammar schools at exactly this time (the late 1940s). The education at such a school would often create distance between a boy and his parents, as he became somebody they “hadn’t raised” and could no longer understand. He would know things they had never heard of, have interests they could not grasp, and speak in a register above theirs.

But in Harrison’s case, all of this was even more pronounced, because the school was not only a grammar but also private. This meant he was surrounded by “posh” kids and immersed in an ancient cultural tradition; the school had existed since 1552. All of this, he now found himself confronted by at a very tender age. It is epitomised by his memory, frequently re-told, of schoolmasters pressuring him to shed his working-class Leeds accent and dialect in favour of RP and Standard English. They wanted to change how he spoke, how he sounded, how he came across to everyone who met him, how he presented to the world.

UNESCO merely wanted him to travel the world, to sup of its novelties and, perhaps, learn from them. One can understand that this open-minded globalism would have seemed a breath of fresh air to Harrison; something innocent and forward-thinking, not dusty and doctrinaire. (Of course, it was still elitist, but it held the promise of democracy and egalitarianism - concepts dear to his heart.)

An ironic point is that the very scholarship which brought him face-to-face with the elitism of Leeds Grammar School was, itself, an egalitarian project, in that it sought to identify the most able among the poor - no matter how poor they were - and help them reach their full potential. This was done by getting them away from the people that would stultify them (their friends and relatives) and placing them amongst their intellectual (if not cultural) peers.

But Harrison did not see it as egalitarian, because the process required him to change, to leave behind the working-class identity and the working-class family and the working-class mentality that he had always known.

Throughout his adulthood, even as he became ever more cultured and less ignorant, ever more worldly and less provincial, Harrison prized his working-class origins more and more, especially after his mother and then his father died, and he sought to honour them.

This has made for a complicated life and a complicated body of work. On the one hand, as a liberal he greatly values civilisation; on the other, as a socialist he hates the infrastructure Britain built to achieve civilisation. On the one hand, he greatly values education; on the other, he wants to be at one with his baker father. On the one hand, he wants to be an enlightened cosmopolitan; on the other, he is still that boy living on Tempest Road in Beeston, Leeds.

This is a man who has serious concerns, and is serious about them.

But he is also a man who has had his time. His heyday was the 1980s and, to a lesser extent, the ‘90s. In the 2020s he is positively a dinosaur - something I will explore in the outro to this series.

Harrison provides a perfect snapshot of British liberalism as it was in the 1980s. He has all the credentials: working-class origins yet educated at a prestigious private school, a poet and artist, high-brow and well-read, a natural traveller, immersed in the creative/media/publishing milieus, and avowedly left-wing (and precisely positioned between Old Left and New Left). In summary, you could hardly ask for a better exemplar of British liberalism at that moment in time.

The sole imperfection is his attachment to place and people. I said he is a natural traveller, but he is not a cosmopolitan. He lives in a quiet adjunct of Newcastle. He clearly has a very strong attachment to homeland. That is already bad as it obstructs globalism, but worse still is that his homeland is England. As Orwell famously noted of the English intelligentsia:

almost any English intellectual would feel more ashamed of standing to attention during God Save the King than stealing from a poor box

Furthermore, Harrison’s attachment is specifically to the working-class - and not the manufactured football-loving faux working-class that politicians now pretend to be at one with, but the racist sexist homophobic beer-swilling genuine working-class of northern England.

His Old Left class consciousness and his love of homeland prevent Harrison from ever being fully at one with the progressive hive mind.

However, such digressions were more forgivable for British liberalism of the 1980s era, and he does make an excellent ambassador of that worldview. To show what I mean, here are his positions on various issues:

strongly anti monarchy

strongly anti censorship

strongly anti religion

anti capitalist

anti racist

anti British Empire

anti America

passively pro feminist

passively pro gay

passively pro multiculturalism (the term “diversity” was not yet in use)

pro democracy

pro welfare

pro miners / trade unions

pro learning, education, civilisation, civility

pro European Union

On every one of these issues, he had the position that was fashionable in the 1980s and early ‘90s. I want to emphasise that I don’t think he was deliberately adopting fashionable positions; I think he was naturally “of the right ilk”.

In turn, Harrison was among the people who shaped my worldview - the people who were in command of British culture in the 1980s and ‘90s, creating things that would become my starting points in understanding the world. Being now a middle-aged man myself, it seems apt to “interrogate” those who guided me in my youth.

A disciple of ‘The Left’ actually pre-occupied with the plight of the British working class. Hard to imagine that such a person ever even existed now. I remember Harrison’s film-poem ‘Prometheus’ being broadcast on Channel 4, way back in 1998, as Blair’s New Labour were setting about their business of dismantling Great Britain. The film begins in a post-industrialised wasteland in Yorkshire - a clear reference to the miners’ strike of 1984. It’s a hugely powerful piece. I lived in the part of Yorkshire worst affected by the mjners’ strike for a number of years. When Margaret Thatcher died in 2013, locals burnt an effigy of her in the old village square.

If the working class thought they had it bad under Thatcher, they’d no idea what ‘the new Left’ had in mind for them. I’d love to know what Harrison makes of Starmer and his cronies. Harrison is 87 now - perhaps he doesn’t care as he’ll ‘be dead soon so it won’t affect me’, the trite excuse made by a good number of that generation. Perhaps he despises the reptilian prosecutor Starmer as much as we do. I wonder what the remains of ‘the old Left’ in Britain think - are they pleased with how it’s all working out?

Wow. Very interesting stuff. I'm in Newcastle and I never knew about any of this