If your mother is still alive and you have things to tell her, tell them. If you have questions for her, ask them. If there is anything you haven’t thanked her for, do so. Most of all, make certain that she knows you love her. Don’t delay.

This is the story of my mother and me. It is that story specifically, and even then, there are other versions that could be told. I have tried to be honest. I am deliberately leaving out some things because they will be told elsewhere and would be inappropriate here. This essay has a specific purpose: to record my perception of her and of our relationship.

As such, this is not “the story of her life”. In that regard I can briefly say that Kathleen Morven Robertson was born in Peebles War Memorial Hospital on the 4th of May 1951. She was half Scottish (Innerleithen) and half English (Spilsby). She grew up in Bo’ness (with spells in Hong Kong and Australia), was the Bo’ness Fair Queen of 1969, lived in Edinburgh as a student, then lived in Linlithgow for the rest of her life with just brief spells in Bo’ness and Aberdeen. She was a primary school teacher specialising in the early years (ages 5-7) and taught at Orwell, Fauldhouse, Kirkliston, Dedridge and Linlithgow Primary among others, and was very well-regarded by colleagues and parents. Those details are all true, but she is not in them.

More personally speaking… She had dark green eyes and curly brown hair “with a bit of red in it” (according to her stylist). She liked Brie and Gruyère and was a “health freak”. She loved watching the little birds in her garden and to see lambs frolicking in the field. She was upbeat, resourceful and devoted to her family and her vocation. She had many friends, enjoyed baking, enjoyed dancing, hated beach holidays and loved gardens. She was respectful of beauty and of the labour involved in creating it. She admired intelligence, ingenuity and creativity. Most of all, I think, she prized honesty and humility. This is closer to describing her, but it doesn’t tell our story.

The irony is, she wouldn’t like to be written about at all. She was a humble and straightforward woman, kind and capable, but with no illusions about being “important” and no desire to be. Neither did she enjoy being praised. But if people like her are not recorded, if people as good as her are allowed to simply fall into the ether, then I don’t think we are doing very well. I owe it to everyone to say something about her. I also owe it to her to straighten out what went wrong - in my life and therefore between us.

This essay’s structure reflects my thoughts around the time of her death in September 2024. The past and the present mingled dizzyingly, and everything orbited around the point when our relationship was cut, in January 2017.

We had always been very close.

But from 2006 onwards, our relationship gradually became degraded by my personal failure. She tried very hard to help me, but a grown man is not a child and there is only so much a mother can do without becoming disgusted. Once or twice harsh words were exchanged, in both directions - she was frustrated with me, I was embarrassed. I think she slowly lost faith in me. I can’t blame her for this. I don’t blame her. I hope - still - to make it up to her.

She retired from teaching in 2012. Granny died at the end of that year, after seven years of dementia. Now Mum’s heavy burdens - of looking after thirty children and an old woman - were finally over. She was free. I hoped she would enjoy retirement.

But both of her parents had had dementia. She knew - we all knew - that this boded badly for her.

Less than a year after Granny died, there was a scary incident. August 2013. A hotel being renovated in Linlithgow got a new front door. Mum mentioned it to me. A few days later, she mentioned it again. A few days later, we were driving past the hotel and she remarked on the new door. I said, “Mum, you already knew about this” and she replied, “no I didn’t, this is the first time I’ve seen it.” Terror struck me. My life wasn’t sorted out yet. I still needed her. I couldn’t bear the idea of losing her. I spent the next four days getting worked up with worry. Then we arranged to meet. When I saw her in the distance, smiling and waving to me, full of life and innocence, I couldn’t help it - I burst into tears. She approached me, wondering what was wrong. I didn’t know whether to tell her. But when she reached me, it spilled out. I told her - what she had done. I expected her to be upset… but instead she smiled and was philosophical about it happening one day, and reassured me that it wasn’t happening yet. Somehow I believed her - maybe because I needed to, or maybe because she was only 62.

And I saw no more signs of it in the three years that followed. But I now know that other people did.

Perhaps subconsciously prompted by that episode, I started working on Millennial Woes just two months later, in October 2013. By this time, Mum wasn’t really interested in anything I did. She contributed money towards the camera - my Christmas present - that would make it possible, but she didn’t ask what I intended to do with it. There had been too many false starts; she had become used to me failing. My esoteric fascinations were more trouble than they were worth, my outlandish plans tedious compared to those of a fondly-regarded teenager, and my despair was an abyss into which time and resources spent helping would only be wasted.

So I didn’t tell her about the channel until about six months in. I don’t remember her being alarmed at all. It seems incredible now, but the truth is none of us knew what I was getting into, or what trouble it would bring to all of us.

I still visited her most weekends through to early 2016. I never noticed any worrying change in her. In retrospect I can see that she was often grumpy and sometimes slow on the up-take, but at the time I thought she was just “getting older”. Others were certain by this point that she had dementia - but somehow they never said anything to me and somehow I remained oblivious.

Then, throughout 2016, my life suddenly and rapidly transformed. Because of my channel’s growth, I had disposable income for the first time in eleven years. I got a girlfriend for the first time ever, and travelled to Germany in March and July. In September, I began travelling internationally to speak at conferences - Rotterdam, Seattle, then DC. The DC conference went awry and became a media sensation, which resulted in me getting designated a hatemonger in the national press back in Scotland, and calls to identify me. I returned to Scotland in early December with this huge threat hanging over me and my family.

Relatives wanted me to shut everything down, delete all of my work, to stave off this calamity. But I had seen other people trying that and it never worked. In fact it was used against them - “he tried to delete the evidence and get away with it!” So I knew that, quite apart from leaving me stranded, destroying what I had built would not prevent the inevitable. And it was now inevitable. It had become inevitable while I and my relatives had been oblivious to the danger. My only hope was that the coverage would be at least fair and balanced - some hope. In the meantime I agreed, sincerely, to tone down my work from here on.

I was soon identified. In early January 2017 journalists and antifa began showing up at Dad’s house where I lived, to get statements and photos of the man whose life they intended to ruin. On the third occasion - the Daily Record’s Alan McEwen with a photographer - I called the police. They arrived and, questioning the two men outside, were informed that the piece was going to be published the next day. I made plans to flee Scotland so as to protect myself and my parents. I couldn’t be at both of their houses at once, so the only option seemed to be if I was demonstrably not in the country at all - then there would be no excuse for harassing either of them.

I went to see Mum one last time. As I explained the very serious situation to her, I was perplexed that she seemed blasé about it. At one time she would have been up the wall with worry about such a thing. I assumed this must be her mellowing with age. I said goodbye, thinking I would see her maybe two or three months later. In fact it would be eighteen months, and by then she would have changed drastically. So really this, as we said goodbye at her front door, was the last time I saw my mother “as herself”. This was the last time I saw the woman I had always known. This was, in a sense, the end of our relationship.

The next morning, Monday, the Daily Record published their major hit-piece, shaming me and, by extension, my family. The language was even worse than I had expected - brutal and vicious. The front cover, plastered with my face, would have been visible in every shop, every supermarket, in Scotland. Suddenly, everyone would “know” that I was an evil man. Those many people who knew my mother would be amazed that she, a humble and happy and respectable school teacher, had somehow produced a monster.

At this point I was in hiding, away from Linlithgow. On the Wednesday I flew to Germany.

Memory 12: “Good as gold” (1980s)

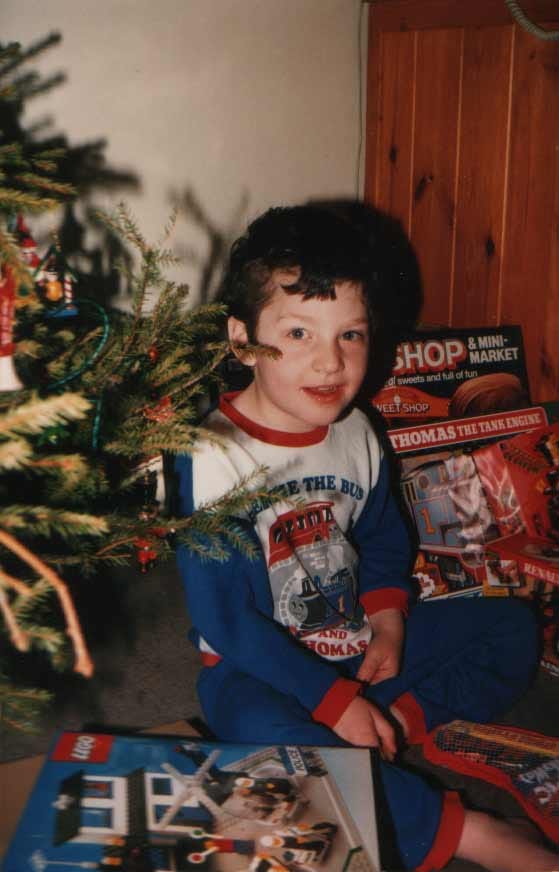

In the beginning there was a single family. I can’t remember much of that time. There was an air of tension between my parents, but I was busy and happy so it didn’t matter much. Indeed, even though my parents were alienated from each other, and even though what followed was good, those first seven years of my life seem idyllic now. We had love, comfort, money and security, and it was the late 1980s - a terrific time to be a small boy.

Mum was organised and conscientious. If she said she would do something, it would be done. She was a firm and sensible but very loving parent. Under her guidance, it was very much a middle-class household, which in those days had a broader meaning than today. We were expected to speak properly, to be clean and tidy, polite, well-mannered, responsible, organised, and to some extent knowledgeable. Discipline was strict. I recall one evening when she walked into the living room and simply said “am I seeing things?” and I knew at once that she was referring to the fact that I didn’t have my slippers on. She ran a tight ship, but I never for a second felt unloved.

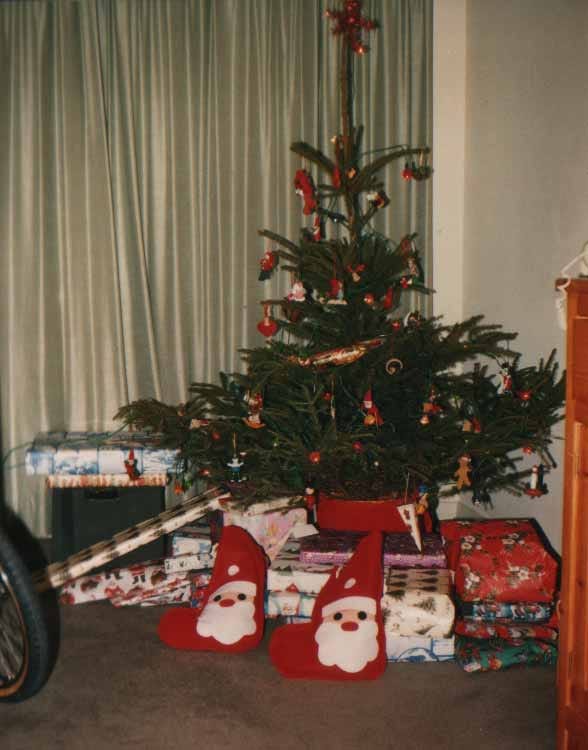

At Christmas, there were felt stockings for the little presents. The felt - so easily sullied, was always immaculate, year after year. Mum was like that.

Christmas presents were wrapped beautifully but not extravagantly. There was love and care but not vulgarity. With this, as with so many other social things, she knew exactly how far to go. I think this was due to good tutoring from her parents but also innate gifts of high empathy and common sense.

Though she was middle-class and a snob, she was full of affection for working-class people and got along with them easily, enjoying their honesty, down-to-earthness, lack of pretension, and brash remarks which she would recount with laughter and fondness. There was always humour in how she described people, even bad people, and for everyone else there was kindness. I could believe she never encountered real evil in her entire life, but the truth is she did - and yet remained open and innocent despite it.

On the rare occasion that she and Dad went to some social gathering, I would be looked after by Granny and Grandpa in their house in Bo’ness. I remember once when Mum arrived to pick me up, and I met her and clasped her hand, cold from the outside air. She asked “how has he been?” and Granny said “oh, good as gold”. Once a frustrated toddler, I had become a very happy and agreeable child, doing well at school and very sociable. People were pleased with me, but they didn’t spoil me and I don’t think they made too much fuss over me. I think the problems I would later face were “baked in”. But we will get to that.

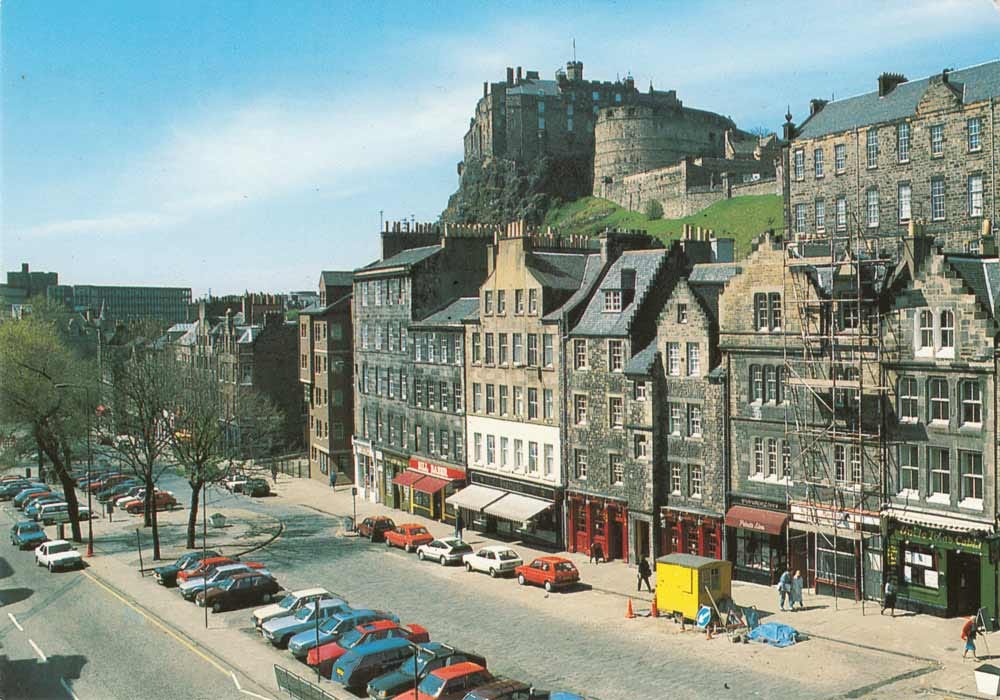

Every Saturday, our family drove into Edinburgh, listening to jolly music on the way. From before my time, Mum and Dad were familiar with the city. Whatever the need, they knew where to go. James Thin for books, Jenners for toys, Studio One for decor, Habitat for furniture, John Lewis for electronics, Marks & Spencer for groceries.

Edinburgh at that time was far from the gleaming “global” city it is now becoming. There wasn’t the tram system, not nearly as many cars, and certainly no ULEZ, so you could drive around freely and park almost anywhere you needed to be. Despite a few small wastelands and dilapidated buildings here and there, it was genteel, and very Scottish - far more authentically so than today.

First we would have lunch at Clarinda’s tearoom, then visit Casey’s for some sweets, then go to Leith Walk for Valvona & Crolla and Harburn Hobbies. From there it might be John Lewis, then Jenners and Marks & Spencer for the week’s groceries. Finally, we might go to the West end for Studio One and Habitat. Leaving Edinburgh through Corstorphine, we might stop at the Duchess sweet shop.

Sometimes we drove home on “the dual carriage”, which meant leaving the city through Stockbridge. Here there was a children’s clothes shop called Baggins. A newsagents sold Creamola Foam. Mum did cross-stitch embroidery, and if she had a picture finished she would take it to an arts shop run by a couple (ahem) of elderly gentlemen to get it framed.

Occasionally we picnicked on the Meadows or Arthur’s Seat. I recall visits to the Chambers Street Museum, the Museum of Childhood, the zoo, and various exhibitions. As a family we were not rich, but we were doing well and we lived well. It was a beautiful beginning to my life.

Present: Nuremberg, 2017-8

Having fled to Germany, I kept regular contact with Dad, but embarrassment and shame kept me from phoning Mum. I eventually plucked up the courage after a month. I was expecting her to be angry and maybe hang up, and I would give her time to cool down then try again. Instead, she was like a different person, almost a stranger, and treated me like one. It was extremely difficult to converse; she seemed utterly uninterested in me. She wouldn’t (couldn’t?) say what I had done, but she knew it was something “bad”. After several phone-calls like this, I began suspecting dementia.

I recall the first moment that idea struck me - March 2017, in an AirBNB in Amsterdam. But blaming it on dementia just seemed like a way to avoid facing the facts: she was deeply upset me with me because I had done a terrible thing. But as I tried desperately to talk to her about that… there was nothing.

I phoned her about twenty times in 2017. On her birthday in May she was upbeat, including about the luxury raspberry white chocolate I had sent her. I thought maybe she was beginning to warm to me again, and things would gradually get better now… but by the next call she had reverted: cold, detached, disapproving, uncommunicative. And she was like that on every subsequent call.

(Many years later I was informed that, towards the end of 2017, she wrote me out of her will. She only reversed this after a lot of persuading by a relative. He believed her decision to cut me out had been influenced by her condition, but he also emphasised that she was “furious” with me.)

In April 2018 I was finally told it was dementia. She had been formally diagnosed the month before, but the people around her already knew full well what it was. Even I, a thousand miles away, knew by this time what it must be. But still, when I heard the word, my heart thumped. The phone-call ended soon after. I sat motionless for some time, digesting it: “Mum is going away now.”

But I couldn’t visit her. The risk to the family was too great. It was made clear to me, freshly, that I wasn’t to visit Linlithgow.

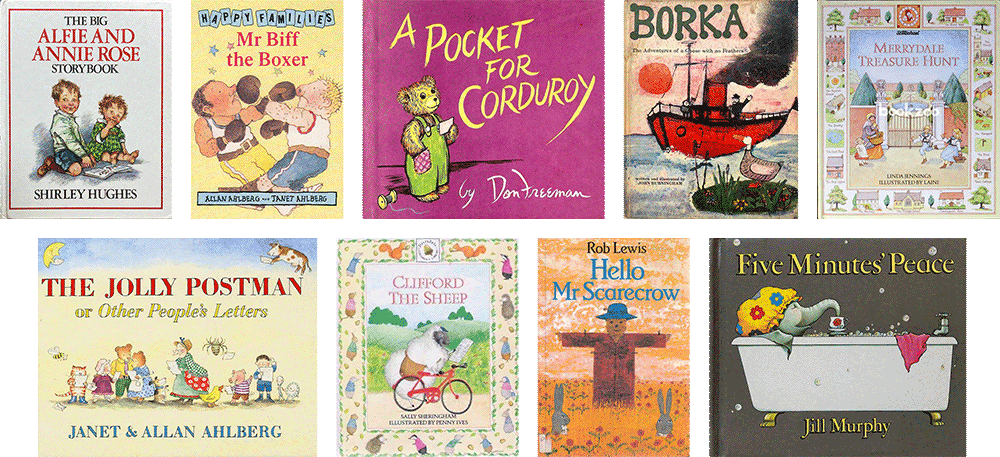

Memory 11: Books and Lego (late 1980s)

I recall one visit with Mum to James Thin at the South Bridge. The children’s department was in the basement, and on this occasion there was somebody doing sock puppetry for families dropping by. Mum and I joined in with delight. Years later she paid for me to go on two puppet-making workshops run by a nice woman called Sylvia Troon. Those were some of the happiest days of my childhood. When I told her all about it at the end of the first day, she smiled and said “I think you’re in your element”. Of course I absolutely relished making things, but Mum believed the appeal of puppets was universal. Many more years later, I recall her declaring “I’ve never known a child who didn’t love puppets”. She wasn’t very creative herself but she greatly valued it in other people and was pleased to see it in me, so vividly.

Little surprise then that there was Lego. So very much Lego…

As for books, this was the era of Roald Dahl, Shirley Hughes, Dick King-Smith, and Janet and Allan Ahlberg. Their work adorned our shelves.

Initially Mum helped me read the books, but I got the hang of it quickly. I knew she was impressed by this and, later, by how well I wrote. She, who had known so many children, was impressed by me. And I so loved impressing her.

But arrogance was kept at bay. She had the sense to do that. I never got away with obnoxiousness. She instilled a very kind ethos in me. I was never as humble as her - and inside was a monstrous ego waiting to be ignited by hormones - but her teachings did take hold.

“Life is all about sharing,” she once told me. It was the philosophy of a woman who had spent her life teaching small children in rural Scotland. Bless her. She was innocent in a way that few people genuinely are. She wanted to be friends with you. She was optimistic, bright, and full of goodness. She had many friends. She could get along with almost anyone. She was open-hearted, trusting, yet not a fool.

Granny told me that Mum first pronounced her name as “Kaka”, then, as she gained language, she added her surname, Wildman, but melded them together as “Kunkywunks”. Granny chuckled affectionately whenever she recounted this. Mum was embarrassed and denied it. Like Granny, I found it hilarious and adorable.

Mum doted on her father, Douglas. He was a highly intelligent man, an engineer who worked for BICC all his life. He was often sent abroad for weeks or months at a time - very unusual in the 1950s - and her favourite memory of childhood was one day finally hearing his car pulling up outside, and running to meet him, blindly, unthinkingly, as fast as her body could manage… and, unaware of everything around her, collapsing into his arms and his love.

She was always very conscious of other people’s wellbeing and went out of her way to help and never to do harm. Other people mattered to her, by default. They mattered so much that, when she was about sixty, she broke down in tears recalling a day in her youth when an adolescent girl was jeered at by rough kids, mocking her for her innocence about sex. All of them laughing and laughing... This violation of an innocent so disturbed my mother, merely a witness to the event, that she cried about it nearly half a century later.

This pronounced empathy was one reason why she was a natural teacher. She loved children. She loved talking about them and their concerns, problems and questions. She enjoyed singing and dancing, organising and explaining. Granny told me that when Mum was little she used to organise the other children, as in a school room. She was born to be a teacher. It was the only thing she ever wanted to be. Moray House called. Hers was the era of the blackboard and the Banda machine. So often, I saw the prints from that - her gentle handwriting in faint purple. Hers was also the era of the hand-written end-of-year reports, personally-worded for each child, and she lamented in the 2000s when it went digital and it became accepted practice to use stock phrases that were known not to cause offence or ambiguity, and each child would receive a set of these copy-and-pasted. It went against her whole mentality as a teacher and carer, who saw it as her duty to know each child well. She loved the job she had dreamed of doing, been trained to do, and done for thirty years… and she hated when it began to change. There were new demands she struggled to keep up with, new tasks she could not master, and old standards she had always respected now being discarded. The bureaucracy expanded after 1997, often with people who Mum said didn’t even like children, and the work became increasingly computerised. Her beloved job was evolving and she was too old to adapt. Certainly by 2006 when I moved back home, she was demoralised and eager to retire.

Ironically, it was her talk of decline - in teaching and in society more broadly - which first “clued me in” to the fact that something was not right in our world. Her concerns, about diligence and diction and devotion, were absorbed by me in my adolescence and over many years evolved into the concerns I have today - things she could not comprehend. Still now, I remain convinced that something like Rotherham could have been guessed at decades earlier when the various hierarchies in our culture were visibly dissolving.

Present: The last of Kathleen, 2018-20

I would finally see her again in October 2018. By this time her coldness towards me had mysteriously vanished, and she was eager to see me.

We met at a quiet bar in Edinburgh, with her chaperoned by her partner. Compared to the day we parted in January 2017, she was clearly different - a look of slight bewilderment, wearing a jacket that she definitely wouldn’t have chosen herself. She seemed vulnerable, a bit unsure, but also clearly delighted to see me again, though she no longer had the facility to express it.

Since we last met, I had been to Nuremberg, Freiburg, Stockholm, Amsterdam, Utrecht, Cologne, Frankfurt, London, Oslo, Dublin, Rotterdam, Vienna, Tallinn, Helsinki, Berlin and Magdeburg… all the places my new life had taken me… but none of that was spoken of. She would never be able to understand the life I now had. Instead, we spoke of the past.

We strolled around the city centre for about half an hour. Then her partner left us for a time. I took Mum to the steps of the Royal Scottish Academy and we sat down there. We were alone. I told her she had been a good mother, and thanked her for everything she had done for me, and told her I would always remember her. What I was trying to convey was profound appreciation. Words could not suffice. In any case I’m not sure she quite grasped what I was saying. She mostly nodded and smiled, but also her eyes welled up a little. She was very happy to be with me again but also sad, and unable to understand her emotion, or at least to express it.

It is possible that, for her, the words were meaningless but the experience was real. Perhaps it is the same for me, really. After all, I can hardly remember anything that was said between us, but I vividly remember the beautiful feeling of being with her. In spite of her condition and the awful thing that had happened to us, the same old dynamic emerged between us - the same laughter, the same affection, the same effortless sharing. We were a mother and a son, but also two old friends. We had been through so, so much together... But all of that was a previous life now, and it was time to say goodbye.

Her partner came back and, after a quick meal at the Waverley Centre, we parted ways.

But life isn’t a movie, and in fact we met again surprisingly soon: March 2019. But it was a sort of “duplicate” of the previous meeting so I remember nothing about it, except the end. As before, we parted at Waverley Station. I watched her, under her partner’s guidance, disappear into the crowds. I watched until I couldn’t see them any more. I wondered when we would meet again, or if, and what she would be like by then. And I thought of how dear she was to me. The way things had gone was so perverse, so wrong.

In January 2020, I visited Scotland again and ventured to meet her in Linlithgow, at home in Dovecot Park. It was the first time I had been in her house since the doxing, and it was the last time I ever would be. It was also the last time I saw her speaking whole sentences, though they were often disconnected from the conversation around her. But her mannerisms remained her own, sometimes pointing into the air to convey emphasis or urgency in her schoolteacherly way. But she couldn’t sit upright and kept falling on to one side, and needed propped up. I did so, sitting next to her and putting my arm around her, like in the old days.

I had brought my new girlfriend along. At one point they were alone together. My girlfriend said to her: “Your son is very special.” Mum smiled and said: “Yes, he is.”

Had she forgiven me? Or just forgotten?

My girlfriend and I left, assuming - of course - that it wouldn’t be the last time. Had I known I would never be in that house again, part of my life since 1991, there would have been some ceremony. I would have gone into each room one last time, and probably salvaged a few objects. Alas, I didn’t get a chance to say goodbye to that house - partly due to my own nervousness about offering help. (Given the state of relations, I assumed such offers would not be welcome.)

Mum declined rapidly over the next few months and, in the May, went into a care home at the opposite end of Linlithgow. It was the same place her mother had died in, eight years earlier, on the same corridor - the room just two doors down.

Memory 10: Arcadia (1991-3)

In 1990, when I was seven, my parents split up. It was awful at the time, with tumult of various kinds. First we lived at Granny and Grandpa’s in Bo’ness. Then Mum rented a flat nearby for several months. Then she bought a house, back in Linlithgow, in the modest but appealing Dovecot Park. Now things settled down, and the new era was nice in its own ways.

Mum was “free” for the first time in sixteen years. She came into her own, adapting her little house. She painted the living room in apricot - warm and comforting. The house was not a compromise; it was very much hers. She began listening to music that a man wouldn’t necessarily like - Nanci Griffith, Mary Chapin Carpenter, Beverley Craven, kd Lang, Emmylou Harris… She saw Suzanne Vega play at the Usher Hall in 1993.

Though I most cherish the time before this when the family was together, this period of the early 1990s was the best time between my mother and me. It is what I think of when I think of her.

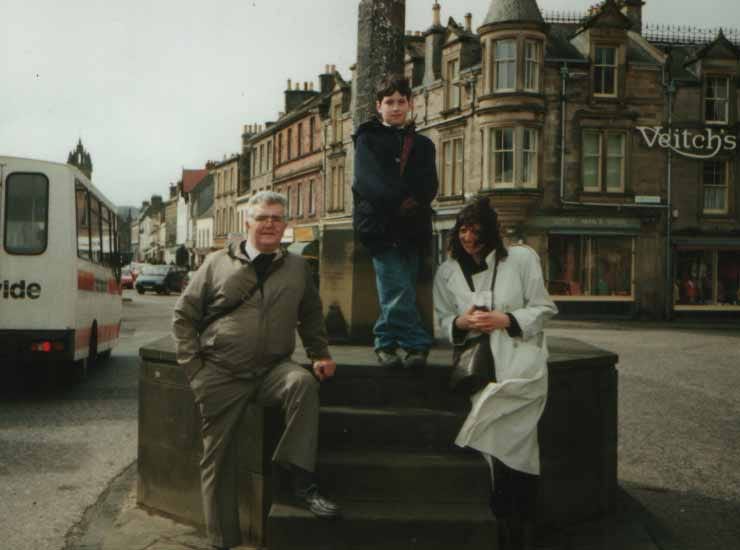

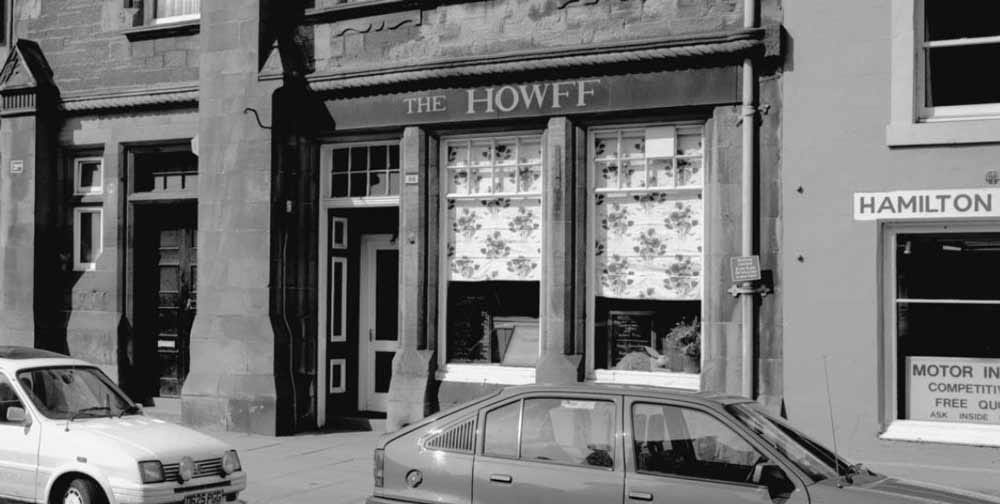

At this time, we would meet Granny and Grandpa once a week at the Howff, a tearoom in Linlithgow. I would also accompany Mum to the Garden Shop (fruit & veg) at the Cross - the woman there was a redhead called Betty - and on her customary visits to the Trinket Box (a gift shop run by sisters Elizabeth and Rosemary), Linlithgow Bookshop (a lovely little shop run by a woman called Chris) and an arts shop called Portfolio Four that had its own tearoom.

By this time my tastes in reading were taking on their own shape - darker things that Mum had no interest in, but she indulged me, gladly, keeping my shelves stocked so that I was always reading. Videos too, by the dozen, and a player in my room.

Wednesday evenings were for grocery shopping. She and I would drive to Falkirk for Marks & Spencer. If Thornton’s was still open we would go there. Sometimes we would instead drive into Edinburgh for the Marks & Spencer there, and also Jenners which had a special place in Mum’s heart. On the way home we would sometimes get takeaway baked potatoes. When the Gyle opened in 1993 its convenience made it our natural mainstay. It had its own Thornton’s, and I remember us enjoying raspberry white chocolates together.

We also continued the old family tradition of visiting Edinburgh at weekends, often meeting up with some friend of hers. I recall rain in Newington, sun in Leith, rain in Stockbridge, sun in Princes Street Gardens. I have a memory of a day (perhaps it is a composite of several occasions) on which we parked in Bruntsfield, met up with one of Mum’s friends and her children, and we all strolled through to Morningside, the weather evolving as we went. We would have gone to Nastiuk’s deli, Studio One’s furniture shop, and places I have forgotten. I would have been quiet sometimes, excited at others, but always feeling safe with her, looking up to her, holding her hand, loving her. That was Kathleen and me. We were so, so close.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Millennial Woes to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.