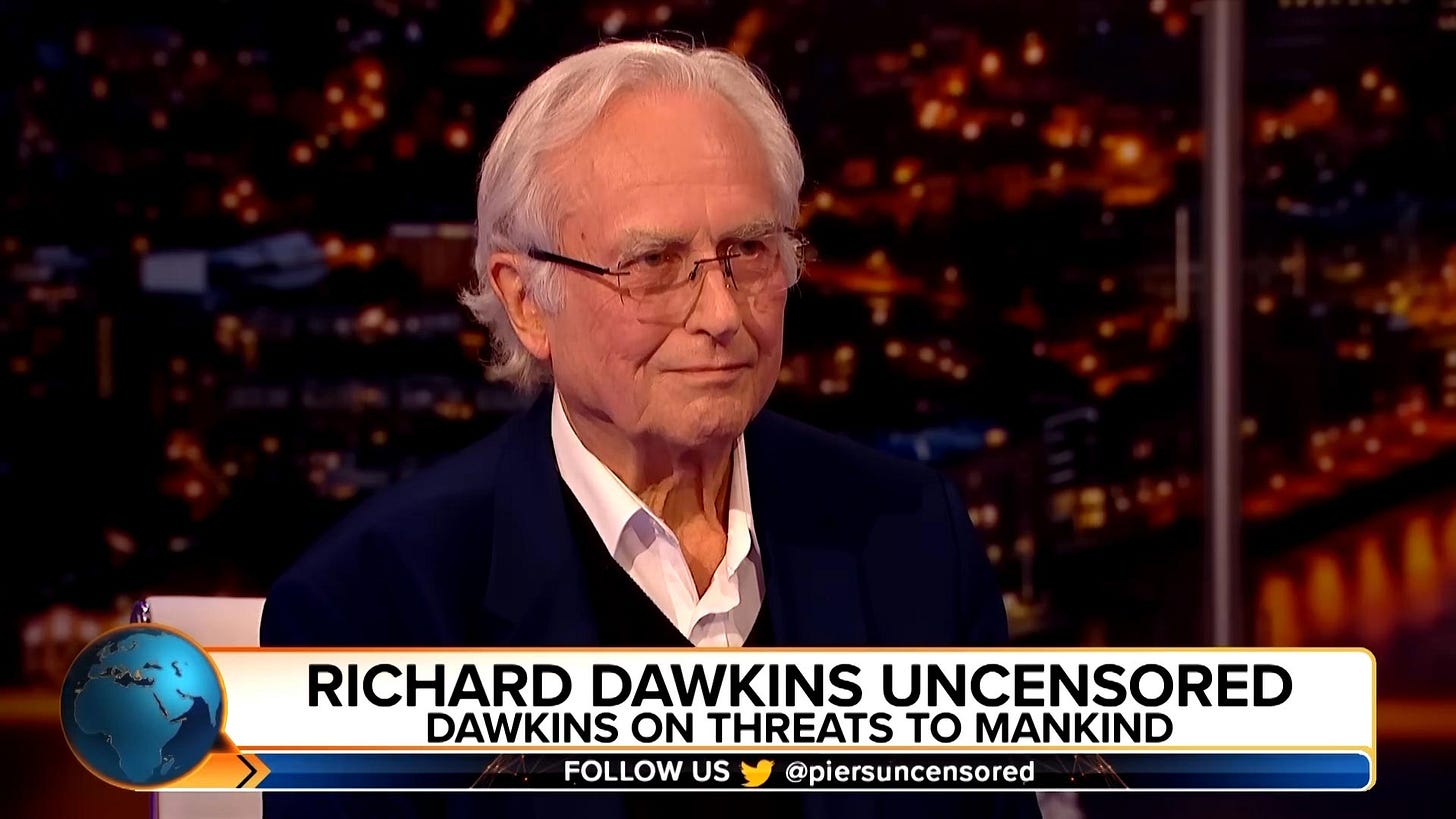

I saw a video clip on Twitter, an extract from an interview of Richard Dawkins by Piers Morgan. Dawkins is asked whether he thinks former “ISIS bride” Shamima Begum should be allowed to return to Britain. He appears literally terrified by being asked this question, and refuses to answer it.

I have been aware of Richard Dawkins for about 25 years, seeing him in many discussions and interviews, and I have never seen him behave remotely like this. Gone is the arrogance, the confidence, the theatrical hand-waving, the dismissive remarks, the haughty tone. In their place, only meek, appeasing fear.

The Twitter clip ended abruptly. Curious as to what was said immediately after the cut, I sought out the full interview on YouTube. What turned out to be much more interesting was what happened immediately before the clip. Taken together, this material merits an analysis all on its own.

First, I would strongly recommend that you watch the video from this point, for 4 minutes (30m-34m). That four minutes of footage could, by itself, explain to historians in the future how the great British tradition of Classical Liberalism died. Or rather, how it was killed.

The material involved divides cleanly into three sections, which I will discuss separately:

Being opposed to national pride

Being opposed to fundamentalist Islam

Terror

From those titles, the storyline might be clear already. It is astonishing how well it is “acted out” by Dawkins in what cannot have been a planned performance. It just fell together this way, as only the truthful can.

1. Being opposed to national pride

Morgan reminds Dawkins of a tweet he made in 2019:

Note that he is speaking here, not about the ideology of nationalism, but about the sentiment of national pride. As well as many tweets demonising Brexit, he has explicitly condemned national pride at least one other time, suggesting it might be “even worse” than religious faith, the thing he has so relentlessly denounced:

You might think, ah, but he can’t be against patriotism in general - only jingoism and jackboots kind of stuff, surely? He must have a place in his heart for gentle, romantic patriotism…? Actually no, he is against patriotism as well.

Now, I fully suspect that Dawkins does, in fact, have real fondness for England, and that his claims to the contrary are just so much intellectual posturing, or the naivety of a man who has never considered that such things could ever be lost. However, let’s take him at his word and assume he really does have no time for nationalism, or even national pride, or even patriotism. That, after all, is certainly the attitude he is trying to encourage in other people.

If everyone with any influence were similarly uncaring about nations, then nations would cease to exist, except as holding pens for the hoi polloi. Ancient nations and homelands would become mere economic zones, wifi-enabled human zoos where traditions were no longer upheld, ancestral culture was no longer preserved, identity was no longer prized or nurtured, objects and places no longer had any value but always a price tag, people no longer had purpose and were therefore lost and depressed and desperately searching for meaning, and the borders, now being meaningless, would be unprotected, leaving the nation open to being swamped by foreigners, who might have all sorts of bizarre ideas that would conflict with the nation’s former way of life.

I am not saying that abolishing national pride makes colonisation from outside inevitable, but that it makes it infinitely more possible than it would otherwise be. That which you do not value, you will not protect, so it will decline. And, if you are dependent on it, you will suffer by its decline.

More concretely: if you do not take the boundaries of your home seriously, then fairly soon, not only will you have strangers living in your front room, you will actually have no grounds upon which to demand that they leave. And, if you are a polite sort of chap like Richard Dawkins, you will probably end up adapting to them, not the other way around.

I will concede that, in the interview, when Morgan requests clarification as to what Dawkins means by “national pride” being a great danger, asking “of the kind that we saw with the Nazis where they literally want to take over the world?”, Dawkins agrees. This implies that he believes only extreme genocidal nationalism is a danger. But, from the many tweets linked above, he clearly doesn’t. He even thinks Land of Hope and Glory would be too jingoistic as a national anthem! He clearly sees any sort of attachment to homeland as irrational, and while it is a matter of degrees whereby the more of it you have the less rational you are, the ideal amount is clearly zero.

Perhaps only a man who inherited, through no effort, 210 acres of prime farmland in one of the most beautiful, idyllic and highly sought-after parts of the country, could think country so valueless.

2. Being opposed to fundamentalist Islam

Morgan asks Dawkins whether he still believes that “fundamentalist Islam” is “one of the great threats”. Once upon a time, Dawkins would have simply replied to this in the affirmative. Here, he immediately broadens it out to all fundamentalist faith.

The objection he voices at this point is the same objection that he has to non-religious ideologies (Communism, Nazism, transgenderism, etc). He does not like people being irrational. He does not like thought systems that encourage people to be irrational. He does not like the unwavering confidence in certain actions that can occur when people are irrational.

I think fundamentalist faith where you believe absolutely that you’re right, without any evidence, is a major danger, because that licenses you to do anything… if you really sincerely believe that you’ve got right on your side, because God told you, then really, I can sort of understand how the Inquisition mind worked, and how the modern Islamist mind works.

At this point, he has criticised religion in general but not Islam in particular. Of Islam in particular, he has been very particular, saying “Islamist” rather than “Islamic” or “Muslim”. The word “Islamist” implies extremist, fundamentalist, and so on, with a bent that is as much political as religious. In other words, he’s not talking about your friendly Muslim shopkeeper, only about the mad ragheads with the bombs. So he is safe, up to this point.

But now is where he makes what I believe he immediately regards as a serious mistake: he criticises Islam in general. It happens because Morgan asks him if he is, as has been suggested in the past, an Islamophobe.

I’m not an Islamophobe. What I am phobic about is clitoridectomy, throwing gay people off buildings, banning dancing and music and having fun generally. I’m phobic about all those sorts of things, but that’s different from being an Islamophobe. Muslims are the biggest victim of Islamism.

In that last sentence, he trips over the opening consonant “M”, extending it slightly, as if a terrifying thought has crossed his mind and distracted him. I believe it has, and I believe the thought was of the attack on his intelligentsia colleague Salman Rushdie, six months earlier. Rushdie is now missing an eye and the use of one hand, after the nerves were severed in an attack which also left him with facial scars. His life will never be the same again.

I believe that Dawkins was in a 2010-esque reverie about the backward demands of Islam, in which he criticised the very doctrines of the religion. Then he remembered about Rushdie. He still seems very much himself at this point, but the change that is about to come is so extreme that I think it must have occurred here. He finishes his point very quickly, presumably hoping that Morgan will now change the topic.

This point in the interview would be a natural time for a change, but surprisingly Morgan persists with the Islam topic.

3. Terror

Morgan now raises a contemporary talking point about Islamism: “There’s been a big debate about this ISIS bride Shamima Begum, whether she should be allowed to come back to this country. Do you have a view about that?”

The camera cuts back to Dawkins, and before our very eyes he transforms. His body language becomes stiff and hunched appeasingly, and when he eventually speaks, his voice is meek, almost a whisper: “I’d rather not say.”

“You’d rather not say?”

“I haven’t studied it enough.” Dawkins says this quickly and firmly. It is obviously a bullshit answer, meant to signal - politely but clearly - that he really does not want to discuss this topic.

Morgan ignores this hint, and begins casually explaining the Begum matter for the man who has claimed not to know much about it: “Well, she was married to an ISIS fighter -”

Very uncharacteristically, Dawkins interrupts: “Yeah, I know -”

Morgan ignores that and continues: “- but she was 15 when she went out there -”

Dawkins interrupts again, saying “yes” quickly, trying to communicate that he wants this topic aborted. He is usually impeccably polite, yet he interrupts Morgan three times while he is attempting to explain the Begum situation.

“- but the debate is was she groomed to be part of this terror group -”

“Yes.”

“- in Syria, and as such should we show mercy and allow her back to this country.”

“Yes. I’m not going to say about that.” Note the phrasing. This is not a grammatical error, but it is slang syntax. With an ordinary person, this would be unremarkable. With Richard Dawkins, it is significant. He is genuinely in fear and panic.

At last, Morgan acknowledges that Dawkins is unsettled. Instead of politely changing the topic, he elects to prod on the matter of Dawkins being unsettled:

“Are you worried about - I mean do you get threats because of the positions you’ve taken on some of these things?”

Were he calmer, Dawkins would probably have responded to this in the affirmative, or said something non-committal but telling, such as “Well, one has to be careful given the current climate.” Instead, like a man utterly terrified, he claims he is not scared at all:

“No…”

He shakes his head while saying that, like a child who has been molested denying he has been molested. It could not be more obvious that he is frightened. Morgan prods further:

“You saw what happened to Salman Rushdie.”

Dawkins affirms his terror, shaking his head again: “No… No…”

“[That] didn’t send a shudder through you?”

This time Dawkins does not speak at all, but shakes his head while silently saying: “No...”

“Are you saying no, you don’t want to talk about it, or -”

Like a man gasping for oxygen, Dawkins says decisively: “Yes.”

I was reminded of the cliché one used to see in films where a hostage is led to the front door by his terrorist captor, to speak to an inquiring police officer and persuade him that everything is normal. Throughout the exchange, unseen by the officer, the captor’s gun is just centimetres away from the hostage’s head, so he diligently says exactly what he has been commanded to say - but tries somehow to signal to the officer that, yes, you’re right, there are terrorists here.

Finally, Morgan shows Dawkins some mercy. “Right. I mean that’s interesting in itself.”

He means it is interesting in itself that Dawkins does not want to discuss the Begum matter. Pathetically, Dawkins denies this: “No it’s not.”

Morgan persists: “There are areas which you’d prefer not to discuss?”

Again, Dawkins answers quickly: “Yes.”

Now there is a long, awkward pause, before he apologetically adds: “I should have said that before we started.”

Recognising that his guest is virtually out of action with stress at this point, Morgan takes the reins for a while:

“Yeah. I mean listen, I think it’s sad that you can’t. I don’t think anything should be off-limits in interviews with people like you. The whole point of the world’s smartest thinkers is we ought to be able to have free and open debate, but I don’t think we do, because people use murderous retribution against free speech. Really that’s what it amounts to, right?”

Dawkins spots a way out: change the subject from Islamism to freedom of speech.

“Well I’m passionately in favour of free speech.”

Morgan runs with that. Now on safer ground, the tone quickly returns to normal.

Caveat

It has been suggested that Dawkins was faking all of this, that he wasn’t actually terrified at all, but wanted to make the point that we can’t speak freely while religious fundamentalists walk among us, because they threaten to commit violence against us if we offend their faith. If so, that does not refute the argument that I will make. If anything it makes things even worse, because Dawkins is showing that he recognises co-existence with Islam cannot work while he simultaneously preaches against having national pride.

Presumably he would say there is no contradiction here: he wants everyone, the world over, regardless of national borders, to be rational and abandon religion. I would argue that this is completely unrealistic, and is being refuted in real-time by our experiences of multiculturalism. If you really want to discourage religion, best to concentrate on your own country and achieve what you want there first, before inviting foreigners in who will make that job much more difficult - but then you can’t be so sensible, because Dawkins rejects national pride!

In addition… If Dawkins was faking in order to communicate to the public that we have lost freedom of speech, what does he expect the public to do about it? It is up to the elite - men such as Richard Dawkins - to foresee these obvious dangers and protect against them. Instead, Dawkins has spent his life advocating mass immigration while saying we are all African. He has utterly failed in what is the first duty of a nation’s elite. The idea that he would now, after the damage is done, appeal to the public to sort out the problem - even while he demonises the only possible solution - makes my blood boil.

In any case, this is all hypothetical. I don’t think Dawkins was faking being terrified. Little things like the grammatical slip seem unintended, and he could have made the same point in a far more dignified way, without making himself look weak and fearful and thus undermining himself as a social commentator.

I believe we are looking at a genuinely terrified man. He recognises that he can no longer speak freely in his home country, yet still adheres to the liberal beliefs that have brought that oppression about.

The storyline

So, what have we witnessed here?

Richard Dawkins is a respected scientist and biologist, and a renowned public intellectual. Even disregarding these accolades he is, clearly, a highly intelligent man. He is, in short, a pillar of the English intelligentsia.

Born into wealth and privilege, he has remained there, being educated at public schools then Oxford before beginning his illustrious career, advancing science, publishing many books, and eventually inheriting an estate.

But he began his life not in England but in Nairobi, Kenya, since his father worked in Africa as a civil servant, one of the last colonial administrators of the British Empire. When the family left the Empire behind and moved to England, 8 year-old Richard seems to have left all romantic notions behind. I suspect the beginning of his disdain for religion was a disdain for nationalism, itself stemming from a disdain for imperialism. Either way, from the moment he began forming his own worldview, it was a supremely rationalist, materialist one. Whether there is romance in his life or not, in his view of social anthropology, there is none; romance there would be irrationality, and might lead him to faulty thinking.

Yet Dawkins is not a man without romance. He has tremendous romance for science, reason and logic. His love for these things is what compels him to be rational; his romance for them is what makes him believe that everyone can be rational.

It is a trait typical of the intelligentsia but perhaps best expressed in Dawkins: the assumption that inside every pleb is an aristocrat just waiting to burst out; inside every ignoramus, a glorious scholar; inside every superstitious fool, a man of reason. This is the apex “luxury belief”, for one can only hold it if one is largely unacquainted with the lower classes, and with the dull conformists of all backgrounds. A lot of trouble in the 20th Century could have been avoided had inquisitive men accepted that their lessers could never be their equals. Even more trouble could have been avoided had inquisitive men accepted that they themselves were fallible. For example, the man who prides himself on cool rationality often has an unexamined predisposition towards its opposite.

This is true of Dawkins, but we will get to that later. The weakness I want to mention here is a different one: naivety. He believes that everyone else can be as rational as he is. In 80 years, he has not noticed that this is not the case, and that there is little evidence to suggest it could ever be the case. Assuming himself wise, he never checked for foolishness. Assuming himself realistic, he never checked for idealism.

Thus it was that, throughout his adult life, he played his part in dismantling and discrediting the culture he had been born into. By the time the dreadful results of this became apparent, it was too late for him to do anything about it, and too late even for him to change. So, the error exists simultaneously with its cause. The man responsible for both cannot correct either, because he cannot admit that he is fallible and has made a terrible mistake.

In the 4 minutes of the Morgan interview, Dawkins demonstrates the entire process simultaneously:

the naive shunning of national pride, which enables mass immigration and the arrival of new cultures into his homeland

the naive criticism of one of those newly-arrived cultures

the terrified realisation that he is now very vulnerable, because the adherents of that culture do not share his English mores (England being the country he professed, in step 1, to take no pride in) and might brutally punish him

This, enacted by one man, is a perfect miniature of the societal experience of multiculturalism.

It is also a wonderfully succinct explanation as to how we got into the mess we are in. Our intelligentsia were arrogant, naive and idealistic, so they embraced ideas that would surely destroy the culture they valued. They didn’t realise the threat of those ideas. They didn’t even realise they valued the culture. They lacked both extrospection and introspection.

Conclusion

During stage 3 in the interview, Dawkins reminds me of a battered wife, an abused child, a hostage… numerous clichés, but all of them weak, tragic, “victim” archetypes. The contrast could not be starker with his usual self. In those moments, he is learning. He is coming up against cold, hard reality - evidence that he cannot dispute, evidence that shakes his worldview.

The question is… what will this rational, logical man do with this evidence?

I’m sure he would prefer to do nothing with it, to just forget that this happened, and pretend that reality accords with his beliefs. But if you pushed him to acknowledge the evidence, his options would be grim:

Admit that he has been wrong. This would be the rational option, but would damage his pride and destroy much of his worldview.

Somehow argue that, despite this evidence, he has been right. This would preserve his pride and his worldview, but would be irrational.

I am confident he would choose option #2.

There are certain things Dawkins needs to believe:

that we all came from Africa / we’re all the same really

that all people are malleable and can be made reasonable

that, inside every Third World immigrant, is an Englishman waiting to burst out

that, nevertheless, England (like all countries) is unimportant

that it is good for man to be without pride for his homeland

that, because we are all the same, we can mix peoples together in the countries we shouldn’t care about

that he is so rational, he can’t be wrong about any of the above, despite its obvious contradictions and its obvious discordance with reality

In order to maintain these superstitions, Dawkins will ignore evidence. He clearly has done so - abundantly. In other words, he is very capable of being irrational. Like a religious person, he has sacred cows, things that cannot be questioned and must be true, and he has the ability to ignore contrary evidence and the willingness to delude himself about doing this. (This is the lie and the covering up of the lie.)

For Dawkins, in the arena of human anthropology, the theory is more important than the data, because the theory accords with his self-image while the data does not. So he is delusional about the data, but more crucially, about his fealty to data in general.

All of this demonstrates another lesson, perhaps the most important of all: only by first being honest with ourselves can we then reflect honestly about the world.

If Dawkins really knew himself, if he were aware of his potential for irrationality and self-delusion, he would know to monitor it so that it did not distort his thinking. But he is not aware of it, so he does not monitor it, and as a result he believes and preaches comfortable lies. When his ceaseless babbling eventually has the effects a serious observer of humans would have predicted, he suddenly ceases babbling, and cowers pathetically and begs for the conversation to change - for reality to change.

Richard Dawkins is an utterly dismal social commentator precisely because he lacks self-knowledge. The results, long after he has passed away, will be horrific.

I couldn't help but comment that Dawkins' trajectory mirrors the lore of Warhammer 40K. A trite point to make, but hear me out.

In Warhammer 40K the Emperor sends out his legions to conquer the galaxy, destroying all aliens, recapturing all of humanity and, most importantly, imposing a purely and rational scientific order on the galaxy. Ruthlessly purging any religions and any notion of metaphysics or superstition.

The problem, is that it's a lie and the Emperor knows it's a lie, that ''Chaos'' is a very real and dangerous threat. Chaos then pushes back, enacting an old plan to corrupt the Emperor's sons and thereby proving the lie. So monumental are the threats and dangers posed by literal hell that humanity is forced back into a mode of religious fundamentalism focussed on the Emperor as a God through sheer terror.

Chaos, irrationality and religion are the norms, not rationalism and Enlightenment values. This was perhaps on Richard's mind during the interview. That in the end irrationality will prevail over your secularism, the other option is to embrace your own brand of it.

Nobody as stupid as an intellectual.