Britain has long enjoyed a reputation for terrible food. That reputation is less deserved nowadays, and in any case was always somewhat over-stated. However, one place where the situation really was very bad was in hospital. Yes, “British hospital food” was as awful as it sounds.

But even hospital food has improved. It makes for an interesting example of the British getting better at “the food thing”, because, as a public service, the NHS has economic limitations that do not apply in, for example, a classy hotel or a swanky international conference centre. There, ample finances are available for on-site kitchens, world-class chefs, the best equipment and the loveliest ingredients. In an NHS hospital, not so much. So a key challenge for today’s NHS planners is to increase the quality of hospital food - since British people have come to expect a higher standard - while keeping the operation as cheap as possible.

Edinburgh’s flagship hospital was always the Royal Infirmary. Housed in a stunning and iconic 1879 building, the RIE was an institution, something the whole city was proud of. In 2003, it moved from its historic location to a brand new building on the outskirts of the city.

The new hospital had no kitchen for making the patients’ food. It was not made on-site at all. It was not even made nearby. Staggeringly, it was made in Wales - 400 miles away - before being transported that distance to Edinburgh. Somehow, the relative costs meant that it was cheaper to do it this way than to simply have a kitchen at the hospital. Distance was nullified by cheap energy costs for motion and refrigeration… and geography simply disappeared.

It reminds me of a tweet by Chris Packham about the perversity of transporting food all over the world when we could simply grow it ourselves.

A 2005 report into operations at the new RIE found the following:

Concern had been expressed by patients about the quality of food and the way it was served. In addition, a Channel 4 documentary had drawn attention to shortcomings at the meal preparation plant in Wales.

A “meal preparation plant”. Doesn’t that sound lovely? Don’t we all love meals made in a “preparation plant”?

The cost of efficiency was end results:

It is becoming increasingly clear that pre-prepared meals - of whatever quality - are being seen as less desirable than meals prepared on site using locally sourced ingredients.

How surprising. Note the sub-clause “of whatever quality”. Patients were not only disappointed by the product: they were disturbed by the process. People like the idea of a process occurring entirely in one area. It suggests a type of efficiency that is more appealing to us psychologically than centralisation across many areas. Why?

Centralisation means the local area goes unused, the local producer goes unpaid and local workers go unemployed. This seems both wasteful and neglectful, contradicting both pragmatism about nearby resources and moral duty to one’s neighbours. Subordinating a thousand distinct “locals” into one singular “global” destroys variety, spontaneity and independence. People are offended by that.

They are also offended by the obliteration of distance and geography that comes with transporting things from central locations; when this is happening, life makes less sense to them.

Finally, people like the idea of self-sufficiency; the idea of cultivating local pockets of function and prosperity. There is something immediately pleasing about the idea of an area taking care of itself, rather than being reliant on support from elsewhere.

For these three reasons alone, localism accords with people’s instincts and globalism does not.

Then we get to the matter of end results. One finding of the 2005 report:

When the new RIE first opened, there were a number of issues raised concerning the catering. Action has been taken to address these, and the provision of food now appears to be well managed, with extensive involvement of both Dieticians and services staff from NHS Lothian, working alongside the catering company.

“The catering company” is a sign of the PFI arrangement by which the hospital had been built and was, in part, being run. In fact, NHS Scotland did not liaise directly with the catering company, but instead via Consort, the private consortium involved.

PFI was a new way of managing public services that came of age during the New Labour era: outsourcing things to external contractors, commercial companies who would find ways to do the job more efficiently because they wanted to make a profit. PFI is a goldmine for private companies and often ends up costing the public purse enormously. To take this one case as an example:

Consort earns £60m a year for running, cleaning and maintaining Edinburgh Royal Infirmary alone, under a contract estimated to be worth £1.26bn by 2028. Under the terms of the PFI deal, agreed in 1997, Consort will still own the building when that contract ends, forcing the NHS either to buy the building, sign a new lease or leave.

Consort was recently criticised for refusing to waive hospital parking charges for NHS staff during the coronavirus crisis, while receiving a subsidy from the Scottish government of nearly £1 million to cover the cost.

PFI is a good example of New Labour being a sequel to the 1980s Thatcher government, under which the publicly-funded BBC was made to seek the cheapest possible ways to do things, including by selling off the family silver and tendering jobs to external contractors. Monetarism, efficiency, streamlining! If it could revitalise the BBC (it didn’t) then it could do the same for another sprawling state monolith, the NHS.

But, this bold and innovative new way to do things had by 2003 led to meals being made in a “plant” 400 miles away, by a catering company making £30m profit every year under the caring gaze of a consortium making £60m profit every year. Incidentally, the catering company, Tillery Valley, was owned at the time by global conglomerate Sodexo.

Despite the bad food quality, centralisation was continued and expanded. In fact, the very company that was disgraced in the TV documentary, Tillery Valley Foods, is still the NHS’s biggest catering supplier today, preparing meals for 120 different hospitals.

In 2014, the Scottish Daily Mail reported:

More than half of Scotland’s hospitals no longer have a ‘traditional’ kitchen where meals are made for patients.

At least 15 kitchens have closed as NHS bosses spend £800,000 a year on cheap bulk-bought ready meals from as far away as Manchester.

… of 128 hospitals [in Scotland], only 61 still have kitchens where food is made principally from scratch.

Those kitchens which have not been shut are mostly used to reheat food from plastic boxes. There have been a flood of complaints about the meals, while three patients a month are starving to death in hospital.

This even included the beloved “Sick Kids” hospital in Edinburgh:

The capital’s Royal Hospital for Sick Children has no kitchen for its young and vulnerable patients.

Incidentally, it’s worth noting that the Sick Kids, another treasured Edinburgh institution, later followed the RIE in relocating from its Victorian building in the city centre to a new building on the outskirts. Compare the lovely 1895 building with the nightmare that (of course) replaced it in 2021:

It’s also worth mentioning that the Victorian building was sold to a private developer who demolished parts of it as well as some adjacent architecture, including a building that was over 160 years old. Whenever you think something might be sacred, there is always a manager disgusting enough to prove you wrong.

To return to the topic…

While the centralisation increased, NHS Scotland did take seriously the complaints from patients about the quality of meals that had been transported hundreds of miles. As a result, “food miles” became a metric by which they judged their operations.

NHS Lothian (a branch of NHS Scotland that covers Edinburgh and surrounding regions) emphasises in this 2014 document an intention to source ingredients locally in future, and to combine them into meals (eg. do the cooking) within Scotland.

By using local suppliers we will be supporting local jobs and local farmers. We want to make sure that we make the most of this opportunity; in this way we will reduce the food miles to the lowest possible level.

It’s not ideal, but it is progress.

It has to be admitted that the document does not seem to have been written by morons or by ghouls. These NHS planners are talking about logistics and efficiency, but also about responsibility to patients. All things considered, they seem well-intentioned.

However, the PFI era continues, and profit-driven external companies are still involved alongside “native” NHS operations:

On some of our sites, including the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, catering is provided by contractors

More ominously, there is no intention to reduce the centralisation aspect. Quite to the contrary:

We currently produce food [for 30 sites] from six kitchens but we are reaching the limits within these. We need to plan for fewer but more modern kitchens.

At least they are talking about “kitchens” rather than “meal preparation plants”, but still, the intention is to increase centralisation, to have even fewer than 6 kitchens for 30 “sites”. Traditionalism isn’t getting a look-in here.

By 2022 the terminology had evolved again. In this detailed strategy document from NHS Scotland, reference is made to “catering production units”. There are 6 uses of the word “kitchen”, mostly negative and to do with “ageing catering estate” - ie. legacy facilities that will be retired.

Frighteningly, there is an obsessive emphasis on reducing “variation” across Scotland, as much as possible. Recipes and processes will be standardised, ensuring the same quality levels everywhere. This is the price of doing anything at scale: you can achieve it, but only by enforcing homogeneity, because only homogeneity can be enforced. If you allow for heterogeneity, you will have (by definition) ceded some control and you will get heterogeneous results. The enemy is variation, because you want its opposite which is consistency, which leads to better predictability, which helps further streamlining, which enables further cost-cutting.

In the document, the word “system” appears 16 times. But, to be fair, the word “patient” appears 70 times.

This is something I would emphasise: as much as we can moan about Blairite managerialism and ruthless logistics, it is obvious that the NHS planners care. Yes, they have targets, but one of those targets is human satisfaction. Managers might have no understanding of the value of old buildings, but they do understand that pleasure and pain, reactions to immediate stimuli, are a thing, and that people have these reactions. In doing their job, they are not blind to the fact that they are ultimately dealing with real human beings. They know they are serving, in both the culinary and moral senses of the word, people.

With that in mind, it is genuinely impressive to see the sheer amount of intelligence, thought and expertise that goes into what is clearly a gigantic logistical problem: delivering 17 million tasty meals per year, across the geographic space of a country, as economically as possible.

It seems that, in tackling this problem, there are two starkly different paths: you can have the cooking done close to the patients and in a highly unoptimised manner (expensive), or you can have the opposite (cheaper). In an almost Faustian battle against reality, the planners seek somehow to do both. The 2022 document shows a repeated desire to:

move the catering services as close to the patients as possible to enhance their catering requirements in terms of choice, timings and suitability

But how can the services be close to the patient, when…

Across NHS Scotland, there are 99 catering production units including Central Production Units producing food with a variety of food production methodologies i.e. traditional cook serves (conventional), cook freeze and cook chill operations

I don’t even know what that terminology means. It is certainly a far cry from the old days.

I realise that hospitals vary - some are huge, some are very small. I can understand why the latter might go in for centralisation of catering, since the needs at each individual “site” will be small, causing a lot of waste. But it seems to me that the big hospitals, at any rate, could do with having their own kitchens.

This 2017 article indicates that NHS Scotland spends about £3.50 on catering per patient per day. Let us assume £2 for the main meal. I am abysmally unskilled in cookery, yet even I can make a tasty and nutritious meal for £2. Granted, with a hospital you would also have to factor in the cost of the kitchen equipment (which would need maintaining) and the on-going costs of paying staff. But, in bulk, would it really be more than £2 for a good meal? That seems implausible to me.

In 2014, Tory health spokesman Jackson Carlaw supplied the proverbial “voice of common sense”:

It shouldn’t be beyond the wit of the Scottish Government to ensure these meals are prepared on site – that would make perfect sense and, over time, value for money.

Ah… but what if it doesn’t?

What if it really is unavoidably more expensive to have a kitchen in every hospital? What if it really is more economical to have “central production units” where processes can be streamlined, recipes standardised, uniformity enforced, duplication minimised, efficiency perfected and economy maximised?

Let us assume, for the sake of argument, that the planners are correct: centralisation saves money and, given small enough “food miles” between farmer and cook and patient, doesn’t reduce the quality all that much. It might be detached and inhuman, but it is efficient.

Assuming that is true, the important question is… how much are we prepared to pay for cosy inefficiency, in order to avoid its cold opposite? Do we just want the food, or do we want something else? And if so, how much is it worth to us?

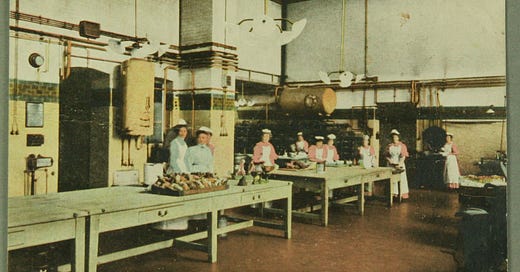

How much does it matter to us that, somewhere in the big hospital we are staying in, there is a kitchen, bustling with activity and peopled by a staff who have known each other for years, with the young temps coming and going and flirting with each other, and the matronly manageress who knows all their tricks, and a no-nonsense chef who knows the best ways to cook the local meats, and that kindly woman who knows just how Mrs McCallister in the long-stay ward likes her egg & cheese sandwich…?

How much does it matter to a woman that she can tell people, including herself, “I’m a cook in the kitchen at the local hospital”? Would that bring her a unique pride and sense of purpose and belonging, or would she be just as happy saying “I work at the nearby NHS central production unit, pushing industrial buttons to make huge quantities of food, to exactly the same recipe every day, that goes into plastic boxes bound for ten different hospitals”? Would there be dislocation and anonymity in that job? How much would she prefer to say, “the hospital, that’s where I work, that’s where I cook for people”?

How much does it matter to the old man in a ward on the third floor, that at 8:30 of an evening he can get the orderly to push him in the wheelchair along the corridor and into the lift, and soon find himself at the canteen, mostly in darkness now because the kitchen staff have clocked out, and that gentle cook who works late has saved a meal for him and will heat it up for him now, on the sly, like she does every evening?

Does any of this matter, at all, to anyone, any more…?

But let’s not get too sentimental. Long before the era of PFI, British hospital food was renowned for its awfulness. This is not something that started when private companies showed up seeking profits. It was there in the era of post-war state monoliths that didn’t care about standards, workers who were lazy, cooks who were unskilled, bureaucrats who couldn’t organise a piss-up in a brewery, politicians who had no interest in actually improving anything. It took the selfishness of PFI to motivate anyone to even improve the efficiency, if only latterly the taste, of hospital catering. The managers seem to take more pride in their planning than the rest of us take in our nation.

If we identified with our country and our people, maybe we wouldn’t need the managers or their damned centralising. If we cared, maybe things would organically be better. Maybe the menopausal cook would take the time to do things well, and learn some new tricks and new recipes, so that the patients weren’t subjected to the most godawful slop. Maybe the serving nurse would know not to splatter the food onto a plate, but to present it nicely. Maybe the hospital kitchen would be led by a man who was no-nonsense, yet also took enough pride in his work that he motivated his staff to go the extra mile, to actually care about what they were doing.

Through decades of post-war decline, none of that ever happened… so eventually the managers were called in - for good and for ill.

We can moan about the food miles, moan about the taste, moan about the presentation, moan about the centralisation, moan that a cook is now a “food technician” and a cosy kitchen is now a “central production unit”… but in the end, we need the managers, because we are a nation that, since 1939, has been on the operating table.

A fantastic anecdote that illustrates why, in general, I began to doubt libertarianism and complete laissez-faire markets. Sure, the libertarian might argue that this is only happening because the NHS is state-run, but there are scores of examples of this kind of soulless corporatism happening everywhere, especially in the US with privately run hospitals, prisons and airports. Sodexo and HMS Host are EVERYWHERE, and no one really knows where all this "food" is coming from.

So, I'm joining the hippie leftist "eat locally" crowd when I can, but for different reasons. The problem with the perverse mixed economy means that small local businesses simply cannot compete in the market with these global giants, especially with the myriad of ever encroaching regulations that seek to destroy them.

The libertarian position is thus to shrink or eliminate the State and do away with these incentives, but of course that ignores the reality of power structures and hierarchies. So yes, I can now unironically say that yes, things would get better "if only the right people are in charge".

In AA's words- clear those in power out and replace them with people who care about the human soul.

I'd also like to add that Woe's point at the end is what I agree with most. Again, from the libertarian viewpoint, opening up to competition and profit will invariably lead to some better results but we see where this is going with the utter soullessness of everything.

To have the kitchen that Woes is talking about, where people CARE, cannot be done with financial incentive or rulemaking or nagging or scolding or nannying.

It must be done because people are good.

It's been my position that politics really doesn't matter as much as the quality of people living in your community, or city, or country. A good people will take care of their neighbors out of genuine care and compassion for them. My father was in a (US) hospital with a severe illness and while the nurses and staff treated him (for the most part) with the kind of politeness that comes from customer service training, it was apparent that he was just patient x who needs this or that treatment at this or that time.

I suppose what I'm advocating for is for people to just start evaluating themselves and how they live their lives and what they find important. Maybe this takes an experience with the Divine. But the social rot we see every day bleeds in to every aspect of our lives, and no amount of money or efficiency projects or votes is going to change that

In other words we get what we fucking deserve. At least, on the whole.