It is well-known that Robocop (1987) is one of my favourite films. I could write about many different aspects of this cinematic masterpiece, but here I will discuss what is, for sociological purposes, perhaps the key line of dialogue in the entire film, the line that enables the whole story to happen.

While the deceased human Alex Murphy is being converted by OCP into the cyborg Crime Prevention Unit 001 “Robocop”, a bunch of corporate executives discuss what they can get away with doing to him during the conversion. How much leeway do they have? How far are they allowed to go? What obligations, if any, do they have to protect Murphy’s welfare, his state of mind, his dignity? How much respect must they accord him, as a human being? Is he still regarded as a human being? Is he still a human being? Will he still be one, when the conversion is complete? If not, are OCP allowed to make him no longer a human being? Is he legally regarded as mere “property” of the corporation? If so, when and by what mechanism did he stop having sovereignty and become property?

There is a dense complex of ethical and legal questions surrounding a private company doing something to an individual - a customer, an employee, etc. As we will learn, powerful corporations have a simple way to defeat this nightmarish Gordian knot of moral conundra and legal trapdoors: persuade the individual to relinquish his rights. Instantly, this eliminates the legal obstacles, resolves the ethical quandaries, and protects the corporation from lawsuits. And it’s all okay, because the individual consented.

Then, the only challenge is in persuading him to do that.

There are many ways. Job security, a pension scheme, lush compensation for his next-of-kin, a moral duty towards the greater good… any of these might suffice. They certainly did for Alex Murphy.

Here is the crucial exchange in the film:

MORTON: What’s the story?

TYLER: We were able to save the left arm.

MORTON: What? I thought we agreed on total body prosthesis. Now lose the arm, okay?

TYLER: Jesus, Morton…

MORTON: Can he understand what I’m saying?

ROOSEVELT: Doesn’t matter. We’re going to blank his memory anyway.

MORTON: Well I think we should lose the arm. What do you think, Johnson?

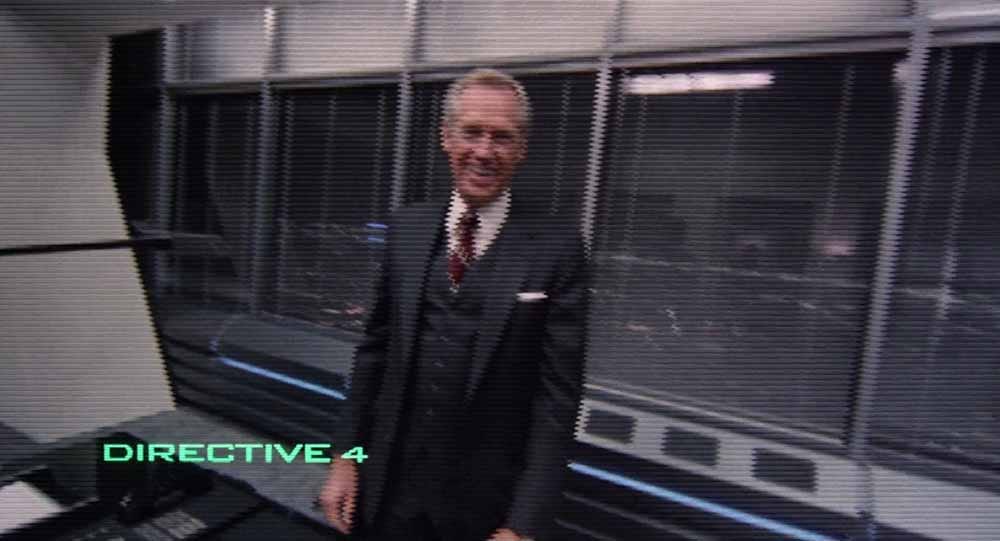

JOHNSON: Well, he signed the release forms when he joined the force. He’s legally dead. We can do pretty much what we want to him.

MORTON: Lose the arm.

As we can see, the legal process that enables OCP to do outrageous things to Alex Murphy has two stages. First, he signs away his and his next-of-kin’s rights in the event that he should die (presumably die on duty, perhaps specifically get killed on duty). Second, he gets killed on duty. With that condition fulfilled, the release forms take effect.

Defining that effect, Johnson’s wording is:

We can do pretty much what we want to him.

Either that means:

We can do literally whatever we want to him, with absolutely no risk of any legal consequences of any kind.

Or it means:

We can do what we want to him, and there might be some minor legal hurdles and a cursory fine or two that we have to pay, but we’ll get away with anything, and anyway, we have the best lawyers money can buy and they can twist whatever legal precedents we require, and by the end we can have his next-of-kin begging us not to make them pay our legal costs for their futile lawsuit against us.

What legal contract could put OCP in such an incredibly privileged position, able to ride roughshod over human dignity? And why would Murphy, an obviously sane man, sign such a contract? Presumably, when he did so, a man being used as the basis for building a cyborg was unheard of so the prospect wasn’t something he even considered. But the forms must have had some clause relating to “use of your body after death”. It was probably something like:

Should you be wounded in the line of duty, OCP will ensure you receive the best possible medical treatment to maximise your chances of survival. In return for this, should the treatment sadly fail, you grant OCP unlimited rights to use your body for research and experimentation with a view to improving the methods and standards of policing.

That would probably cover what OCP eventually did with Murphy. After all, they used his body for experimentation with a view to improving policing. He had granted them unlimited rights in this experimentation, so they had no obligation to preserve his arm; indeed, they were free even to needlessly amputate and discard his arm, should it for whatever reason suit their purposes to do so. They were similarly free to alter his brain so as to “blank his memory”. All of this is covered by “unlimited rights”, which, to the ordinary man signing the form on an ordinary day, would seem a quite reasonable thing for his employer to request. After all, Murphy wants policing to be improved - he’s a good man - and of course his employer doesn’t want legal problems in pursuing this worthy goal. And anyway, what difference will it make to Murphy what is done with his body when he’s dead? As for his family, they can have a funeral one way or the other - it makes no difference to them either. In any case, if he’s dead, they’ll be far more concerned with that than with some experiments being done on his corpse, experiments which will benefit everyone.

And if all that carrot fails to persuade, there’s the stick: if he refuses to sign the release forms, he can’t work as a police officer and will have to find a different job, one without the generous benefits.

So, as outlandish as the conversion from Murphy to Robocop is, realistically, most men actually would sign the forms that allow it to happen.

And with that consent given, OCP is freed from morality, ethics, and a truckload of legalities. (What yuppie wouldn’t buy that for a dollar?)

The concept of consent looms large in the second and third acts of the film, as Robocop finds himself forcibly constrained by prime directives that he never agreed to, and realises that he was once a man, and grapples with the fact that two sets of people altered him against his will: the criminal gang who murdered him for kicks, and the corporation that converted him for profit. He never wanted any of that, and we are meant to agree that it all happened without his consent.

But, as we have seen, he actually did consent to being converted - he just didn’t realise at the time. That specific horror was buried within a cloud of far more mundane alternatives, and was unknowable for him when he signed the forms. But, from the legal point of view, that is no defence. Alex Murphy consented.

The concept of consent looms large in our own world today. By default, you have all sorts of rights… When you are born, your society might decree that, whether by God or by nation, you have Right X, Right Y and Right Z. These rights are yours. They cannot be taken away by force, but you can give them away by choice. You might sign a contract which legally nullifies your claim to Right Y. Thereafter, you no longer have Right Y, so you should not behave as if you do, nor expect other people or organisations to behave as if you do. You relinquished Right Y. That means you are no longer in the same legal position, no longer the same type of citizen, no longer the same type of lifeform, as someone who has not relinquished Right Y.

A legal document, properly formatted and phrased, and a dotted line to which you voluntarily put your signature, suffices to transform your legal position in any number of ways. After the fact, you cannot complain; you consented. If you could still complain, then legal documents would have no weight at all. It is in the nature of legalities that they change actualities, otherwise there would be no point to them whatsoever. So, if you consent to not being treated with dignity, the corporation is not obligated to accord you any.

Robocop is constrained by prime directives which limit his free will, degrade his dignity, and in extremis, shut him down. This is okay because he is “product”. It would not be okay if he were human, because we want humans to have free will. Robocop did not consent to be constrained, but Alex Murphy did consent to become Robocop. Once his signature was on the form, whatever happened next, however monstrous it was and however objectionable he found it, he had no legal right to complain.

In the real world, Murphy and his family would have some legal recourse. They could argue that, though he gave consent, he could not possibly have predicted what that consent would be used for, so it was unreasonable for OCP to use it for those purposes. OCP would still have a good defence to make against this in court, but they might well lose.

This would hinge on how much latitude they had bought for themselves by the wording of their contracts.

But law is more than contracts. Discretion is understood to be necessary in juggling the rights and responsibilities of the various parties involved in a dispute. This is what judges are for. Therefore, OCP’s winning or losing the case would also hinge on how much influence they had over the judge, or the politicians who control the law to which the judge must adhere. But what if the police union also had influence over the judge and was determined to fight for Murphy? Bad news for OCP. Extra leverage could be gained for them if they had influence over the media that was reporting on all of this. If Murphy was very unlucky, OCP would also have some sway with the investment firms that control everyone’s livelihoods.

Of course, the worst-case scenario for Murphy would be if OCP, the judge, the police union chief, the politicians, the media and the investment firms were all in a club together. But that scenario is so outlandish, so conspiratorial and paranoic, so laughably improbable, that not even a writer of 1980s pulp science-fiction would degrade himself with such hackneyed nonsense.

I have gone through this in such detail so as to show that OCP’s lack of criminal liability in Robocop is much more plausible than some might suppose, and to lay the groundwork for comparing with real corporations in the 2020s.

If OCP’s ability to get away with crime seems unrealistic, consider what Pfizer, Moderna and Astra-Zeneca got away with in 2021 and 2022. Two years after the roll-out of their covid vaccines, the death rate in Britain is currently 20% above normal. The global corporations responsible for this have legal immunity so cannot be sued for malfeasance or negligence. This immunity was granted to them by the national governments, which were acting “in a panic” due to an official “state of emergency”.

The public did consent to this. They consented directly and individually when each one of them freely went along to receive the vaccine. They consented indirectly and collectively via their elected governments. True, all of this only happened because of massive and overwhelming pressure from the mainstream media - full-spectrum dominance of the narrative - but to claim that such propaganda absolves the public for consenting is to claim that Alex Murphy didn’t really know what he was getting into, and that he could just as happily have got some other career. No, he really wanted to be a cop. He wanted it so much, the selfish bastard, he was prepared to sign any old forms. So he did it willingly. And, just like he really wanted to be a cop, the pandemic-stricken public really wanted to be safe, so like him they were easily duped.

Many are now dead as a result - much deader than Alex Murphy. And just as OCP persisted, so Pfizer persists. Albert Bourla hasn’t even bothered to delete this tweet. He’s not worried at all.

There is a metaphysical dimension to all of this. At the height of the covid era, certain people were invoking the Book of Revelation:

And he had power to give life unto the image of the beast, that the image of the beast should both speak, and cause that as many as would not worship the image of the beast should be killed.

And he causeth all, both small and great, rich and poor, free and bond, to receive a mark in their right hand, or in their foreheads.

And that no man might buy or sell, save he that had the mark.

There is ambiguity here about how much choice people have in the matter. The beast causes them to worship him and become “marked”. Likewise, Pfizer caused people, by use of propaganda and fearmongering, to accept the vaccine, yet can still say that nobody was forced. This lack of compulsion seems to be integral. The deal must be agreed to - if not entirely freely, then at least with the option to refuse. In the judgement of some cosmic order, it is not good enough to impose damnation upon the public by force. If they are to consent, it must be allowed for them to refuse. They cannot be damned by others, from outside; they must damn themselves.

(Similarly, in Nineteen Eighty-Four, the Party cannot truly destroy Winston except by getting him to betray Julia. They cannot destroy him from outside; he must do it to himself. So the Party’s ultimate task is to get him to do that. They will push him as far as they can, to the very limit of their ability to coerce - but in the end, he will take the final step himself.)

The trick is to make the option to refuse as grim as possible. In the prophecy of Revelation, those who do not bear the mark will not be able to trade, so normal life will be impossible for them. Similarly, during and after covid, the elites claimed that nobody was being “forced” to get the vaccine. This is true. However, if you wanted something resembling a normal life - go to a cafe, enter a supermarket, keep your job, see your relatives, meet with friends - you had to consent.

And yet still, even given that coercion, people were inviting the Devil into their homes by choice. There was always the option to say no.

There had to be, because otherwise the consent would be meaningless.

The covid scamdemic brought all of this to an extreme level. It is almost cheap to invoke it, because what happened is so obviously outrageous.

More subtle are the ways in which huge online platforms rope you into unreasonable relationships with them.

To use any of these platforms, you have to agree to everything laid down in a set of documents - terms & conditions, community guidelines, acceptable use policy, platform policy, etc. These documents govern what you can and can’t do on the platform, but also modulate your status as a citizen of your country by requiring you to consensually give up certain rights.

For example, to use Instagram, you must agree to the terms. One of those is that, in the event of a legal dispute between you and Instagram, the case will be heard in Ireland. The catch is that the Irish government is in lockstep with social media corporations, including the giant Meta corporation which owns Instagram. What are your chances of getting a fair hearing against Instagram in an Irish court? But you must consent to that, if you want to use Instagram at all. The Meta corporation has re-fashioned the world to suit its needs.

In theory, everyone is giving “informed consent” because the terms are there to be read before you click the “agree” button… but in reality, who actually reads those reams of text? People are fickle and there is always something more exciting to do than carefully read hundreds of pages of mind-numbing legalese.

In theory, anyone can say no to these terms... but in reality, there are no viable alternatives to these platforms. For example, for making a career as a video blogger, the only platform any sensible person would want to use is YouTube. No rival video-sharing platform comes remotely close to it in size, user base, brand recognition, public trust, familiarity, ease of use, etc. so, to all intents and purposes, there is no rival to YouTube. Similarly, there is no Pepsi to Twitter’s Coca Cola. Therefore the vast majority of people are going to say yes to whatever terms in order to use the platform. While this is a consensual decision, it is one that people are virtually compelled, by circumstances, to make. Do you “need” a YouTube channel in order to live? Of course not. But you do need one if you want to live as a video creator on a level playing field with all other video creators operating today. So the alternative to accepting YouTube’s terms of use - ie. giving up certain legal rights - is giving up your place in the modern world.

In theory, terms that have been revised cannot be enforced if the individual has not newly consented to them… but in reality, the corporations have wangled another advantage for themselves: they can simply include in their terms that, if the individual continues using the service after the terms are revised in the future, that constitutes acceptance of the revised terms. There is no need for the user - no requirement, no temptation for him - to read the new terms by which he is now expected to adhere. He’ll find out what they are when he breaks them. Nor is there any need for him to sign a new dotted line; the assumed signing of future dotted lines was contained within the original contract, and agreed to when he signed that original dotted line.

In October 2022, there was a brief controversy when it was reported that PayPal was going to begin fining users for spreading “misinformation”. That term, of course, means “anything the regime disagrees with”, which could encompass any number of things - climate change denial, covid denial, vaccine resistance, so-called transphobia, opposition to the Great Replacement, etc.

It turned out to be a false alarm. The policy had been published “in error”. In fact, PayPal only reserve the right to fine you up to $2,500 if you have been engaging in fraudulent or illegal activity.

What is significant is that the claim was plausible, plausible enough that many believed it was real. It seemed entirely in keeping with PayPal’s stated social goals, after all.

It would also be entirely possible. PayPal could legally do this to its users, because they would have consented to it by accepting the platform’s terms, which they do simply by continuing to use the platform after the revised terms have been introduced.

So, if PayPal wanted to do this, technically, they could. I wrote at the time:

It’s as much as $2,500 per “violation”.

This seems like a great way to bankrupt political dissidents. Let you do your thing, collecting maybe a few hundred dollars in PayPal donations, then suddenly fine you for 10 mildly “hateful” tweets. Immediately, you owe them $25,000, when you probably don’t have any money. You can’t complain, because it’s in the terms & conditions which you agreed to, so you have consented to all of this and are now in a legally-binding contract to pay $25,000 to PayPal. You could take PayPal to court, but they can effortlessly afford the very best lawyers alive while, by contrast, you are literally penniless. You are now bankrupt, and it is all legal and above board. The system has ruined you [a political dissident] financially, there’s nothing you can do about it, and all it cost them was the time it took some blue-haired intern to find 10 tweets.

Your only recourse would be a long, grueling, financially ruinous court case against PayPal, in which you would have to argue that your 10 tweets did not constitute hate speech. You wouldn’t be able to argue that their policy was unfair or illegal or in violation of your rights to freedom of speech, since you had voluntarily consented to it. PayPal - and the law - would be no more obligated to respect your freedom of speech than OCP were obligated to respect Murphy’s arm.

This is how a corporation can do what the state cannot: persuade a citizen to give up rights which are otherwise naturally his. They chip away at the citizen, removing this right, that legal recourse… until he is “ideal”.

If a corporation operates internationally, or even globally, the same consent form can simply be duplicated for each country. It might be worded a little differently here or there to neutralise nuances peculiar to each legal system, to perfectly detach the individual from the rights that are normal in his particular country, the legal protections fashioned and considered natural by his particular people.

Those protections continue to exist and be recognised, celebrated, even deemed sacred, so the state cannot be called irresponsible. It’s simply that the individual can consent to be separated from these protections. The corporation must perform this cut with surgical precision, so the wording in its contracts must be perfect. It means the difference between legions of lawsuits and zero lawsuits.

Contracts are the means by which the corporation converts raw humans into ideal clients, whether as employees, customers, partners, assets, or whatever. Since the conversion is indeed consensual, the client effectively does it to himself, while the corporation stands back and watches, blameless. It merely offered the contract; the raw human accepted and signed it, thus converting himself into customer, employee, partner, asset, or in the case of Alex Murphy, material. With that material, OCP manufactured a product. Had Murphy retained his sovereignty, no product could have been manufactured.

But it’s not all bad. After all, sometimes corporations use their materials to create a better world for everyone.

The individual’s loss of protections is the corporation’s gain of function. By successfully reducing his sovereignty, the corporation increases its own.

The individual’s waiving away rights is the corporation’s freedom from consequences. By persuading him to underwrite the future, the corporation frees itself from responsibility and, in a sense, from reality.

As I go over all the bills and statements and announcements and changes to this or that plan or arrangement or contract that have flooded into my mailbox recently, it occurs to me that this is a form of concerted action. Corporate managers have collectively determined to overwhelm us with fine print. We can't possibly read all this crap, much less meditate like some 18th century aristocrat on the implications of the content. Yet we can't do so much as download an update to Adobe Acrobat without "signing" a contract. We are conclusively presumed to have read, understood, and agreed to every lawyer-drafted word, and yet everybody knows that none of us reads this. Not even Ron Paul -- so don't start with me. And the more of these contracts we get, the less likely it is that we will read any of them. So corporations have an incentive to send more of them and make them longer and more verbose. This is a collective decision on their part, and it is working, and they know it.

Nearly all of this stuff is enforceable, as many an HOA or condo unit owner has discovered, and it makes citizens relatively powerless. The private logic of contract law structures the relationship as individual consumer vs. big corporation with government as the enforcer of the contract, instead of citizens vs. powerful private organizations, with government as policy maker holding jurisdiction over the relationship.

The law calls these boilerplate documents "contracts of adhesion," but the days are long past when judges were willing to throw them out because they were drafted by one party and imposed on the other, there was gross inequality of bargaining power, and there was no real assent to the terms. Now they are deemed essential to the free flow of modern commerce.

My view has always been that policy makers should be willing to step in and reform these relationships if they become predatory or destructive. But there is little stomach for that presently.

- Evan McKenzie, J.D., Ph.D., "The Fine Print Society", December 22 2011

@ http://privatopia.blogspot.com/2011/12/fine-print-society.html

Great article, and yes Robocop remains a classic. Its message is even more applicable today than when it came out.