Lurking despised in the annals of horror cinema history is a 1995 film called The Mangler, adapted from a Stephen King short story (readable here). It is about an industrial laundry press that is, to just come out and say it, possessed. This ludicrous concept enables much gore but also gives the film its comic notoriety.

The adapting was done mostly by the film’s director, Tobe Hooper. Usually a short story does not provide enough material for a feature film so the screenwriter will flesh it out, make things more complicated, add a sub-plot, etc. With The Mangler, the additions are interesting because they give the story a political dimension. King’s original is a cleverly-written, effective and surprisingly terrifying vignette. Hooper’s film is a badly-executed, low-grade gore-fest, yet it has the audacity to also offer a political critique of America.

This essay is not a general review of the film. I will discuss only its political critique. I should say that it is a clichéd and one-dimensional critique. Right-wing viewers of The Mangler will have been rolling their eyes at it for the last 30 years. My intent is to show them that, in fact, there’s a lot of truth to it.

Note: Virtually everything I will discuss here is absent from King’s story and unique to the film. This includes the town, the social structure, the back-story, Pictureman and all of the blue-blood characters. (Gartley is merely mentioned in King’s story, not described at all.)

Note: I do not claim that Tobe Hooper intended any of the below interpretations.

The setting is a small town in Maine. Rikers Valley looks nice enough, but beneath the surface is decay - of every kind. We hear mention of the Puritan history of Maine and this town particularly. Witches were burned nearby - part of the area’s “narrow-minded” past. In the opinion of a progressive character, the “Puritanical ethic” still hangs over the town, and it breeds corruption. And as we will see, the town is thoroughly corrupt.

In Rikers Valley, there are only two social classes. You are either an oppressed worker or a rich scumbag who keeps the workers oppressed. There is nothing in between. Of the film’s characters, most are poor. The rich are represented by the corrupt Judge Bishop, the corrupt town sheriff, a corrupt doctor, and corrupt town patriarch Bill Gartley.

Gartley is a deformed, cackling old maniac. He owns the Blue Ribbon Laundry, at the centre of which is the eponymous “mangler”, a gigantic “speed ironer” that billows steam and sucks up human resources throughout the film’s duration.

Gartley runs the business with cruel disregard for his staff. They suffer, they are abused, they are worked to the bone, they have no prospects except through obedience to their superiors - and the prospects are only that they might one day be promoted to a position where they abuse their former peers.

Obedience, yielding a sickly reward that only means you get divided from those with whom you feel natural kinship, and are compelled to hurt them. This is a system that punishes the human.

That’s life at the Blue Ribbon Laundry, but also around the town generally. Everything in Rikers Valley is rotten and nasty. Nothing happens without a price tag. There is no social conscience. Ordinary people have little to look forward to. They expect to be lied to and are rarely surprised. They try to be kind to each other, to do each other a favour now and then, but it is more and more difficult, because life is taking more and more out of them. Many of them are sickly and hooked on cheap tablets that don’t cure anything but ease the pain, a bit, maybe. Their town is going to shit - profit from regenerating it would take too long to show up on the balance sheet. There is no thinking of the long term. And as for the various social problems that are manifesting like maggots on a corpse… well, why sell one cure when you can sell a dozen palliatives?

In short, the spirit of Bill Gartley inhabits every corner of Rikers Valley. This is not just because he has influence, more because the rest of the town’s blue-bloods are just like him. They are all connected to each other, they marry into each other’s families, they help each other out, a nod and a wink to keep things “just so”, and of course they all look down on the workers. In short, they all uphold the same cruel, inhuman system.

But it is not a system they serve, nor a way of life or a tradition, a creed or a religion. They serve a demon.

Upon initiating a protégé into the demon cult, Gartley says: “You’re one of us now. Welcome to the club.” The allusion is to country clubs, exclusive organisations, the traditional mainstays of WASP social life. But it is not wealth, ancestry or education that brings you this life, but allegiance to a demon. Then, power and status are bestowed upon you.

Gartley represents every left-wing bogeyman about right-wing America: capitalistic, ruthless, self-interested, cruel, scheming, snobbish yet uncultured and ignorant, nepotistic, reptilian, materialistic and shallow. And there is no nuance; he is wholly bad. Of noblesse oblige, he remarks “survival of the fittest is the way of things” and “there’s no free lunch, no siree, not in this lifetime”.

He is obsessed with making profit, but he prizes power above mere money. Ultimately, he serves the demon. Such is true of all the blue-bloods in Rikers Valley.

The demon, in turn, is housed within the mangler. It lives inside the machine, receives sacrifices via the machine, and in extremis can reconfigure the machine so that it can get around and cause havoc.

The life of the blue-bloods is not carefree. They too suffer. Gartley talks frequently about the need to “make sacrifices”. He even sacrificed his own daughter to the demon. That is something it demands of everyone who seeks power, and all the patriarchs of Rikers Valley have obliged.

But it demands another sacrifice of them, too. There is a sort of “confirmation” ritual that initiates them into servitude. It involves the demon taking a small piece of their body, the tip of their right ring finger. (Given the similarity here to brit milah, it is amazing how close the film gets to “noticing”, and how sharply it draws away from that to home in on a different target.) Then again, the involvement of hands, of hands being altered so that the person can be recognised by other cult members as a fellow, is suggestive of the famous “secret handshake” by which Freemasons allegedly recognise each other.

In the course of this initiation, the demon also gives the person some tiny piece of itself - and thus they are bonded.

The protagonist is warned by an old, wizened, terminally ill character, Pictureman, to watch out for people with missing body parts; old-timers in Rikers Valley said that those people are of the demon, and will be dishonest and cruel in service to it. (Presumably then, the demon was in the town before the mangler arrived.) Pictureman is also the one who explains about the daughter sacrificing that has long gone on in the town, though how far back is not specified.

You might wonder how Pictureman has this knowledge. His refined accent is a clue. His talk of needing to forgive yourself for past misdeeds, and to exorcise your demons, is another. The proof is subtle but certain: if you look closely during his death scene, you can see that his right ring finger is truncated.

This is interesting because Pictureman is undoubtedly a good man. This means that the bond with the demon does not obliterate your free will. However, it does give the demon great power over you. Only once I realised that Pictureman was initiated did I understand that his terminal disease - “the doc says I’m going fast, being eaten up inside” - is the demon itself, punishing him for defying it.

Pictureman’s final act is to vomit triumphantly, finally ejecting the demon from his being.

In the case of Gartley, the demon has done far more than take his right ring finger. His left eye is missing, his ears are twisted, his hands are permanently gloved to conceal God-knows-what, a deep scar reaches around his neck centring on his larynx, which is studded with a metal bolt, and his legs are, well, mangled, requiring braces to hold them together and that he use two crutches to walk. (Of course it’s baffling how a laundry press could possibly inflict these injuries, but whatever.) The demon has made a cripple of Gartley.

And yet, he is devoted to it. In one scene, he shows his protégé the “contract” he long ago made with it. The paper is titled “certificate of ownership”. It is clear that in his perverted state, he feels great pride about this contract. He loves the demon and relishes serving it.

It should be said that his devotion is not simply selfish. While the demon is the source of his personal power and security, there is also a social element involved. “Chaos abounds,” he says. Only order can combat chaos. And the demon, by bonding individuals to it, and thereby to each other, creates order in Rikers Valley. It is the centre from which all order in the town emanates.

So for Gartley, servitude to the demon is all that matters in life. He is of good breeding, but high culture is of no interest to him. Never do we see him listening to classical music, commenting on art or literature, or making a reference to ancient history, let alone the Divine. He lives completely in the here and now, and is frank about that. He does have some time for luxury but one gets the impression this is mostly to signal to everyone else that he is of higher status than them. At work, he wears a pinstripe suit. In the evenings, he wears a velvet smoking jacket and is surrounded by old books. But those old books might contain nothing more ennobling than numbers and facts about how to exploit people. Not for Gartley, the dreaming spires of Cambridge or the Grand Tour of Europe; he would chuckle at such short-sighted indulgences.

Thus it makes sense that Gartley’s successor - his adopted “niece” Sherry - is not some urbane blue-blood like him. The ruling class of Rikers Valley have been like that until now, but the demon doesn’t care about such things. It only requires loyalty. So the uncouth, unrefined Sherry is going to run the Blue Ribbon Laundry from now on, and the demon has remade her in a Gartley-esque image - limping around with a crutch, missing a finger, and ranting about driving the workers hard to maximise profit.

Sherry replaces Gartley after the demon has killed him. Why it does so is not entirely clear. I think the idea is that he was trying to persuade it to give him more life by sacrificing another young woman. He has no more daughters to give, which is probably why he adopted Sherry in the first place: when the time comes, the demon will be placated by her blood and give Gartley what he wants. But the demon sees Sherry as leadership material, so kills Gartley along with his protégé.

Gartley’s final words are to curse the demon he has served all his life. But it’s too late. He dies, Sherry takes his place, and the demon remains in control of Rikers Valley.

Rikers Valley, as a society, has lost sight of what matters in life, because all efforts have been diverted to serving the demon. A parasite is in charge. The result is that everything is slowly falling apart - crumbling infrastructure, dilapidated roads and buildings, short-termist thinking, a public exploited by an elite that despises them and feeds them bad food, bad medication, and bad morals.

Tobe Hooper clearly intended the town as a metaphor for America. Whether he believed the country had always been this way, or started well but became this way, I don’t know.

He sees American society as enslaved to a demonic system, which he would call “capitalism”. In his view, the country is effectively a gigantic corporation. Just as the social structure of Rikers Valley is optimised for serving the demon (and thus breeds stagnation and decay), the social structure of America is merely the organisational structure of a corporation. And the only point of American society is the continuance of the corporation. As for the people - the workers and the blue-blood class who manage them - they are just the corporation’s human resources.

In a key scene, Gartley says:

My power has nothing to do with money! Power is energy. Power is motivation. Power is what holds things together, when they would rather fly apart!

Hooper presumably intends us to find this reprehensible and false. But I think it is true. It sounds reprehensible only because it lacks the surrounding justification.

The natural state of things is chaos, therefore things would naturally fly apart. Only order can prevent that. Order can only be imposed and maintained by power. Therefore power is necessary. And, since all else is chaos, power works.

If you are not backed by power, all the laws and all the money will not save you against those who are.

Hooper wants to believe that the natural state of things is not chaos but goodness, but by the end of the film he has conceded that this is naive. Without power, goodness cannot ever win.

In 1995, America was doing so well economically that even liberals lost sight of things beyond consumerism. Who cares about community, meaning, heritage, identity, when the Pepsi-Cola tastes so good? And look, Windows 95 is a terrific improvement on Windows 3.1 - this society works! Everything is getting better and better!

In such a context, The Mangler’s political critique was never going to be popular. It’s a distillation of many tired left-wing clichés: ruthless capitalism, nasty corporate America, nasty traditional America, nasty blue-bloods, a society that doesn’t care about people only profit, villains at the top spewing poison down into the capillaries of the society, etc. It’s the kind of critique that seemed obsolete by 1995. The anti-corporate stuff was “discredited”, the anti-tradition stuff had become superfluous, and the class war stuff was irrelevant in a society where class simply equalled wealth and anyone could become wealthy.

But the good times did not last. Wealth became concentrated into ever fewer hands. It became clear that “anyone” couldn’t become wealthy, and that corporate capitalism fillets everything out of life - community, tradition, heritage, meaning. By 2010 America (and the whole West) had moved from the era of old-fashioned capitalism to globalist corporatism, which rode roughshod over the familiar, the organic and the local in a way that hadn’t really manifested in 1995.

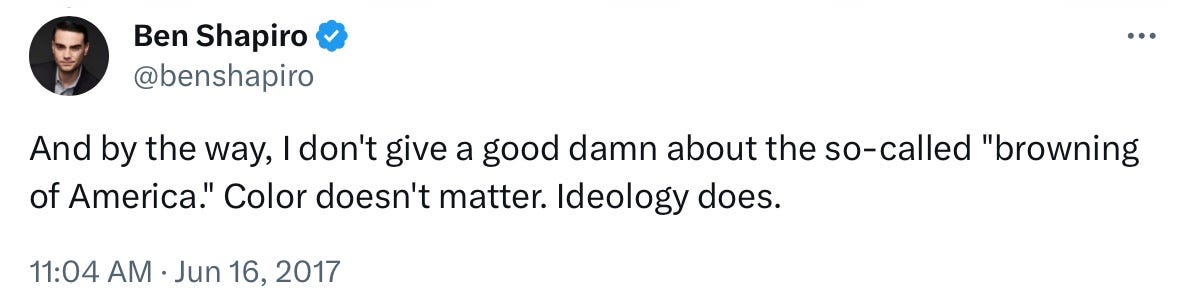

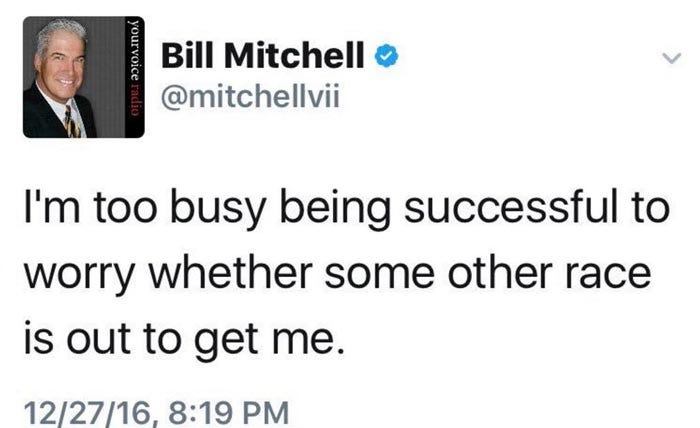

People had to be prevented from turning against all of this and back towards heritage, identity, community, and so on. Ways were found. The Left were distracted by Big Capital donning the rainbow regalia. The Right were distracted by the Neocon dream of exporting “freedom” abroad and reaffirming individualism at home. Awful figures like Ben Shapiro emerged to remind right-wingers not to fall for collectivism of any kind. It’s all about values - the values of freedom, individualism and prosperity - that’s America!

Neocons, while constantly ginning up financial support for Israel, successfully persuaded right-wing Americans that to blame capitalism or individualism for “systemic problems” in society, or to imagine there are such things as “systemic” problems, or to want the state to fix them, is to be wrong, cowardly, collectivist, utopian, irresponsible, and a kind of superstitious SJW moron.

Most of all, neocons mocked the very idea that social problems could be caused by your economic system. As for the idea that there is some cabal at the top conspiring to degrade everyone below… well, it’s all just a bit paranoid, self-pitying and lazy, isn’t it?

And yet… it’s true. Clearly, problems in society must be caused by corruption at the top. Everything that happens in society happens either because it was decreed by the rulers, or because the rulers failed to notice it or prevent it. In either case, they are responsible. And if a social problem remains unsolved or even gets deliberately worsened, that too can only be due to decisions at the top. It was not naive of left-wingers to believe this, it was naive of right-wingers not to believe it.

And what’s more, organised evil can only be defeated by organised goodness. That too is something right-wingers are beginning to realise. It was always naive to think that, against all the odds, good would somehow just assert itself eventually, or evil would one day get tired and just give up. It was even more fanciful to think that the invisible hand of the free market would somehow solve cultural, social or moral decay.

Furthermore, Hooper in The Mangler paints an accurate picture of how a society gets wrecked: a minority group practices nepotism, initiates its young into the cult by means of a small bodily change, works its way to the top of the social hierarchies, and then spews poison downwards to weaken the body politic, turning their culture rotten and exploiting them into oblivion, in service to some goal which is irrelevant to that majority but crucial to the (now ruling) minority because it secures their power and status.

But of course, America is not exactly like that. In truth, most of the lawmakers and bureaucrats are not of that minority group. This is where Jeffrey Epstein (and others like him) come in: by means of blackmail, he brought blue-bloods under control. With enough operators like him, and with well-enough selected targets, you quickly have an entire society corrupted, destroying itself for the betterment of a foreign minority while distracting itself with short-term trinkets.

That is Rikers Valley, but it is also America today, and it is all of the West today - from Sweden to Italy, from Britain to Finland. All the politicians, the corporate leaders, the charity CEOs, the co-opted celebrities… all the public figures who purport to care for “the people” and for society as an entity, are in fact serving something else entirely, something which feeds on those people and those societies while driving them into the ground. The rulers of Rikers Valley are no more serving Rikers Valley than Grant Shapps is serving Britain, Joe Biden is serving America, Justin Trudeau is serving Canada, Jacinda Ardern was serving New Zealand, or Angela Merkel was serving Germany.

Tobe Hooper got the whole thing exactly correct - clichéd and cringe and simplistic though it is. He only mis-identified the ruling minority.

However, the old WASP blue-bloods whom he blamed are not entirely innocent. Sure, they are not in charge today, but it was on their watch that America - and thereby the entire West - got corrupted in the first place. In that sense, The Mangler’s critique is a hundred years out of date. America was corrupted, not in 1995, but at least as far back as 1913.

Corruption is a concept that right-wingers should understand easily, and should be able to believe is a real and present threat to their society. Awareness of corruption comes very naturally to the conservative mind. But in recent decades they have been trained to scoff at the concept as somewhat superstitious and highfalutin. Thus, they reject the entire notion of society as a thing that needs to be protected from corruption. This keeps them ineffectual. If you do not recognise systemic problems as being such, you can never solve them.

Earlier I described America as “a society where class equalled wealth and anyone could become wealthy”. Class came to mean nothing but financial level. This has probably always been the case to some extent in America, but it is much more so as the very idea of cultural hierarchy is subsumed into mass capitalism. All that matters now is efficiency, function and popularity. We have no hierarchy by which a thing could be judged in any other ways.

In the real world, we see constant cultural decline. Your handwriting is probably not as ornate as that of your parents, which in turn is inferior to that of your grandparents. This decline affects everything from manners to cultural tastes to thought itself - what Humanities professor today can hold a candle to his predecessors from 1890? But we see it most obviously when people at “the top” of our society behave in a plebeian way:

This is a poison that is not unique to globalism or corporatism. It is there in capitalism itself. Capitalism doesn’t care about manners, refinement, hierarchy, civilisation, transcendence… indeed, these things get in the way of profit, so they have all fallen away as capitalism has become more and more refined, and more and more the only “paradigm” in our society.

This process is reflected in The Mangler. Gartley is “old money”, raised in an upper-class environment, yet he has no interest in high culture, thinking only of money and his duty to the demon. He is eventually replaced with the unrefined Sherry, because the demon doesn’t require class, only loyalty and efficiency.

Capitalism equalises people in a much more insidious way than Communism. Under capitalism, moronic mediocrity is celebrated while anything beautiful or refined or rare is despised, and encouraged to mix itself with the common and base.

And so, just as this demon separates people from each other, it also separates people from transcendence. Paradoxically, it both ruptures the symbiosis between classes and dissolves the classes into each other. Structure is gone, leaving only rank competition of the most base kind. All else has fallen away. There is only the demon, and its countless meat-servants.

The Mangler is a film that flopped on release and did not become a cult classic afterwards. That is to say, people hated it then and they’ve hated it ever since. Why is obvious. The acting is mostly dreadful, the Gartley character cartoonish, the gore excessive, the central concept laughable, and the plotting somewhat clumsy. People also found the critique silly and irrelevant. I hope I have made the case that, their other complaints aside, they were wrong about that.

Very interesting piece, Woes.

We seem an inherently hierarchical species (but what species isn't?). A management consultant I talked to back in Germany told me that when he was brought in to help with problem companies/departments, 100% of the time it was down to bad leadership. Even with so-called emergent behaviour, the leader must encourage or discourage such things, there's no getting away from top-down responsibility. Thus, in a sufficiently horrific society one might as well hypothesise a "demon" as guiding principle, whether a malign non-human intelligence is literally at work, or if "demon" is just a word we use for certain patterns of human thought & motivation.

Anonymous Conservative noted that we've found evidence of child sacrifice all over the planet, as if totally isolated, disconnected populations spontaneously decide that they can accrue some benefit from killing babies.

I've come to believe these malign intelligences exist and interact with us; that they in some way require our suffering & relish our degradation. There are the isolated cases of influence, e.g. a serial killer; even worse, they occasionally seem able to influence an entire society through conventional material means (propaganda etc). My guess is, those at the very top of society have some ritualistic means of interacting with such an intelligence, and that ritual has become a means of in-group cohesion, like wearing a badge or having a secret handshake. I prefer not to speculate too much but there's so much purposeful evil about us now, that I can't just shrug and say "yeah people are weird, it must be emergent behaviour".

Next time someone asks what happened to my hand I'll whisper, horribly, "Tell me, how do you feel about industrial laundry presses...?"

Truly a fascinating essay. I think it's remarkable that you're able to glean so much insight from a frankly mediocre source. I rented the movie via old school Blockbuster and remember dismissing it as typical Stephen King hatred of traditional America.

I found this bit in particular very interesting:

"In the real world, we see constant cultural decline. Your handwriting is probably not as ornate as that of your parents, which in turn is inferior to that of your grandparents. This decline affects everything from manners to cultural tastes to thought itself - what Humanities professor today can hold a candle to his predecessors from 1890?"

This is true. It is so true and so tragic and so bizarre, and when you mention it to normies you get the sense that they can sense it too and yet have been conditioned to not think about it too much. Pursuing it to it's logical endpoint is embarrassing. References to 1984 have become more than cliche at this point, but I'm reminded of how the regime was able to not only make certain ideas illegal but to even make them shameful.

Still I think that eventually the disparity between what we have NOW vs what we had THEN will be impossible to ignore. The other day my daughters and I were watching an old movie set in the 70s and they asked me what it was like back then. I told them, we had way less people back then (our country's population has doubled via immigration since I was born), and nearly everyone was white. My younger daughter said, "Honestly that sounds really nice."