I have said elsewhere that Tony Harrison was the perfect 1980s British liberal. However, there is one caveat: he had sympathy with White working-class English people who felt marginalised by mass immigration. This was voiced in a poem that will be examined here and, less delicately, in his 1987 film-poem V.

His home city of Leeds is now 21% non-white. His ward, Beeston, is 35% non-white. The street he grew up on (Tempest Road) is in the present-day ward of Hunslet, which is 44% non-white. In the 1940s, when Harrison was a child, both areas would have been virtually, if not literally, 0% non-white.

It may be that this transformation would not bother Harrison at all, were it not for the fact that it did bother his ageing father.

He published Next Door in his Continuous collection of 1981. The full text will be included and examined here.

First, I should state that I am not attempting to paint Harrison as a “racist” or a “closet xenophobe”; I believe he is a liberal and a committed one. However, I do believe that, were he more honest with himself, he probably would have become anti-immigration. If anything, I am criticising him for not making this transition.

It is important to note that we are not discussing the various abstract results of mass immigration - sky-high crime rates, economic damage via welfare dependency, anti-White racism, cultural dissolution, state expansion and intrusion into daily life, mass grooming of White children, corruption of democracy with block-voting, demographic replacement - but instead a very human and humble thing: the fact of an old man feeling alienated on his own street, feeling swamped with the foreign and the hostile, feeling forgotten by his society and neglected by his government, and spending his final four years in confusion, isolation and worry.

Harry Ashton Harrison’s fate is one that must have already befallen many hundreds of English people. (This was a full decade after Drucilla Cotterill in Wolverhampton.) Around the country, in this town and that city, the same process was playing out or had played out, and it was old people who often bore the brunt. Their options for escape - “white flight” - were very limited, so frequently it would be an old man or woman who was “the last White on the street”.

Liberals who observed this probably told themselves it was just a teething issue, that immigration would settle and ever fewer old English people would suffer this fate. They were wrong: immigration has never settled but has constantly increased. As a result, from 1981 to 2024, every single year there have been more old English people seeing out their lives in this terrible isolation.

Harrison grew up at No. 120 Tempest Road. His parents remained in the house all their lives. His mother, Florrie, died in 1976. Next Door tells the story of the house from Harrison’s perspective, centred around the final years when his father, Ashton, was living there on his own.

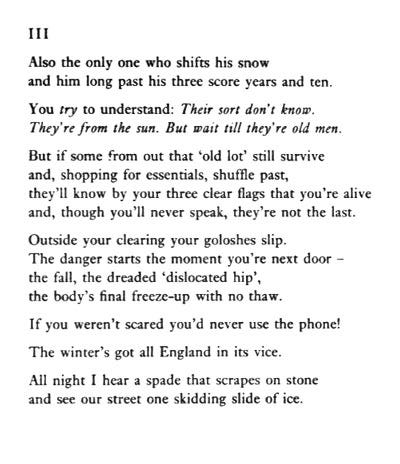

The poem is written as four “stretched sonnets” (16 lines). The four will be examined separately.

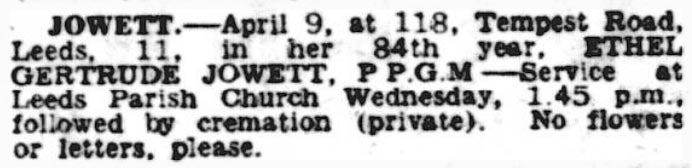

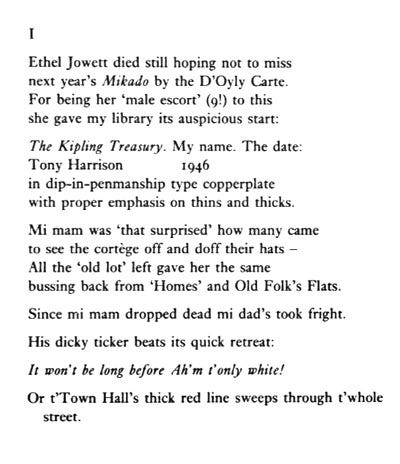

Harrison begins talking about his house by talking about the woman who lived next door, with whom his family obviously enjoyed close friendship for many years. This was typical between the households in such neighbourhoods. Their aged neighbour, Ethel, was an aficionado of Gilbert & Sullivan opera, staged by the D’Oyly Carte. She wanted some company when she attended one year. Presumably her brother, with whom she lived, was not interested in opera, so she asked the Harrisons if little Tony would be her escort. She thanked him with a gift, the book that began his library:

She wrote his name at the front, in practised calligraphic handwriting. Such unnecessary ornament denotes commitment, of some form, of whatever form a woman like her could manage, to the project of civilisation. It is not only for aesthetic reasons that one gives “proper emphasis on thins and thicks”, nor is it done merely to impress other people. It is to uphold the cultural infrastructure by which “proper” emphasis is decreed. If we do not have that infrastructure, no standards can be decreed, and then how will we know what is “proper”? Ethel Jowett, a probably not very well-educated spinster, understood this.

She was obviously a character well-known and well-liked, for her funeral was well-attended. People bussed in from surrounding areas and nursing homes, people who had known her in previous eras, unknown to young Harrison.

Decades passed, and eventually his mother died, in 1976. Since then, his father has been at No. 120 on his own. But things have moved on terribly since Ethel Jowett’s time, 22 years earlier. Thanks to mass immigration Tempest Road would be unrecognisable to her. There on his own, old Ashton is scared.

The line in italics is a quote from him. (There will be more such lines later.) The old man exclaims, impotently, that it won’t be long until he is the only White resident on the street. Already, he is the only one on his block.

Were this the only such quote in the poem, Harrison would be alluding to his father’s “racism” but only obliquely, and then switching to topics less uncomfortable. But in fact, he does not give himself, or the reader, such convenient escape. As we will see, he dwells on his father’s situation. This is a liberal writer trying to reach back to his roots, trying to be at one again with the father from whom he feels separated by his education. He is desperate to understand, but also desperate not to agree.

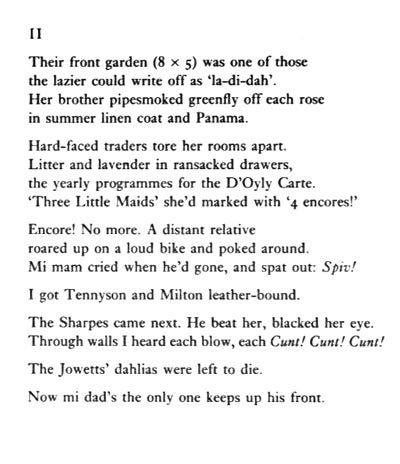

The first stanza deserves explication. Beeston at that time was working-class, but what was called respectable working-class. The residents of such areas had some aspiration about them. Nowadays aspiration among working-class people is called being “upwardly mobile”, meaning desirous of material betterment, but back then, it meant an appreciation of civility. This requires acceptance of the concept of civilisation. Ethel’s brother would carefully remove the greenfly from her roses, wearing a linen jacket and a Panama hat. Such people did not necessarily aspire to wealth, but to being civilised, self-sufficient and “pro-active”. Residents of Beeston, such as Harrison’s family, understood that you can have a nice garden; you just have to put in the effort. They also understood that some people - “the lazier” - can’t be bothered putting in effort and instead settle for feeling envy, which makes them resentful and scornful of those who do put in effort. This is the “crabs in the bucket” mentality that can hold working-class people down and is why some seek to move to areas, like Beeston, free of such negativity.

Harrison tells us what happened to their little abode after she died: it was ransacked by tradesmen looking for anything valuable. Her theatre programmes, bearing her handwritten notes, were ripped out and dumped - the stuff of a life, scattered and destroyed.

There is something beautiful in the fact that, amidst this disarray, young Harrison received from Ethel’s belongings leather-bound copies of Milton and Tennyson - a precious seed of civilisation passed from one worthy bearer to another when it could so easily have been lost.

Some anonymous relative showed up to see what he could get from the house. Harrison’s mother was upset by this mercenary treatment of Ethel and Ernest Jowett, whom she had known and he hadn’t.

There are sociological undertones to this. It is an individual moral blight, but it speaks of the wider social decay that was now taking place in England, and which would swiftly (by four lines later) evolve into demographic breakdown.

In the meantime we see more of the social decay. The couple who move into the Jowetts’ house, the Sharpes, are in a dysfunctional marriage. The man is violent to the woman, and the sound of him beating her is heard by young Harrison through the wall. They fight, and in “their” garden the flowers that Ethel planted are allowed to perish. Beeston is still working-class, but it is less respectable.

Twenty years later, the Sharpes are long gone, replaced with immigrants.

In the final line we get the first indication that racial change brings cultural change, and sometimes of a negative sort. The people on Tempest Road have changed, and this has made the values change, as civic nationalists fondly imagined it wouldn’t. Ashton is one of few White people left on the street, and he is the only resident who still looks after the appearance of his house. This was a source of pride and dignity and a sign to peers that “we are respectable”. This social convention, once ardently adhered to by the urban English working-class, has vanished along with the urban English working-class. Of those who remain, all but one have abandoned the convention because it no longer matters; the people who would receive the signal are no longer present, so why send the signal?

The residents did not wait for the council to shift snow for them, because they knew it would turn to ice before then, so they shifted it themselves. Now old Ashton is the only one who does that. As his son notes, he tries to understand why his new neighbours neglect this task. They come from warmer climes, so they have no experience of this and don’t know what will happen - even though they have by now been in England enough winters to learn. He says they needn’t care for now because they are still young; ice is not a great threat to them.

“Three clear flags” refers to flagstones (paving slabs) cleared of snow. This used to be just good housekeeping, but now it is a signal that the resident is English - a signal that will be baffling to the newcomers but understood by any other English who happen to see it. From this sight, they will draw reassurance, knowing that they are not alone. But they also know that the conversation about their newfound isolation will never be had, even with those who share it. They are too isolated even to draw companionship from each other - and after all, what use would it be now?

The ground that belongs to other residents and is left icy by them is now a serious threat to Ashton. If he slipped, it might be the end of him. He lives in a constant state of worry.

But on the bright side, this makes him phone his son more often than he otherwise would.

But on the dark side, hearing about his father’s situation makes Harrison worry. He imagines the old man obsessively keeping his own plot free of ice while, all around him, the street promises to send him tumbling to a mortal injury.

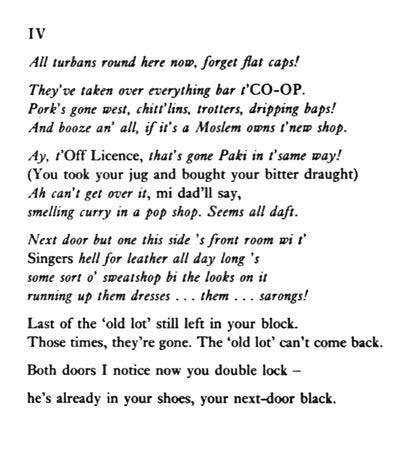

Flat caps, the traditional head wear of the working-class Englishman, have given way to turbans. “They” - not just Muslims but also Sikhs and Hindus - have taken over all the little shops that used to make up the local community. Only the Co-op remains in English control, but that too will soon change.

The traditional foodstuffs that Ashton has always known have disappeared (“gone west”). This includes everything made from pig meat - pork, chitterlings, trotters, dripping.

The off-license, a staple of British life for well over a century by then, has been bought over by Pakistanis. The shop now smells of curry and Ashton can no longer take along his jug to get it filled with bitter beer, since Muslims won’t sell alcohol. Their aversion to it is something that Ashton just has to accept; there will be fewer and fewer places where he can do something he has always done. Now he has to bear in mind the differences between Muslims and other foreign groups - things he never needed to know before.

“Singers” refers to a sewing machine. Ashton is annoyed at the constant sound of the machine. It is two doors along but he can hear it “all day long” and presumes that the family must be running a sweatshop making sarongs, a word he struggles to remember since it is foreign and new to him.

Ashton is the last English person in his block of terraced houses. The life he knew is gone. The old White English neighbours “can’t come back” - that community can never exist again.

The final adjective refers to any non-white neighbour, not necessarily Black. (Back then the adjective was used in this way.) It is a very unsettling final line, showing Harrison to be fully aware of how demographic change torments old people, and of how futile it is for his father to hope to stave off these newcomers indefinitely. They are “already in your shoes”; you double lock your front and back doors, but they might as well already be in the house; in many ways they have already taken your place. It is no longer the foreigner who is foreign on this English street, but the Englishman.

By the time this poem was published, old Ashton had died.

No doubt it was indeed non-whites who were living in his house by the time those lines were printed onto paper, memorialising the misery he endured at the end of his life.

Thanks so much for returning to the work of Tony Harrison. After your last piece on his work, I felt I was a bit harsh on Harrison in the comment I left. I speculated on whether he was one of those boomers that doesn’t care as they’ll be dead by the time all hell is let loose. I agree with you - I think this poem shows that he does care about what happens to the white working class from whence he came. It’s an incredibly moving piece. Harrison did not sentimentalise the white working class either - his depiction of the wife beater next door was all too real.

Like you, I feel frustrated that he and others can’t take that final step and actually come out and say that mass immigration has been a disaster and a crime against all of us. He’s 87 years’ old now - what would it cost him to tell the truth?

‘And so the kingdom of Gondor sank into ruin, the line of kings failed, the white tree withered and the rule of Gondor was given over to lesser men.’ - JRR Tolkien

This is such a powerful and haunting post.

It beautifully illustrates the deep melancholy that has overtaken so many Northern towns—fuelled by the slow, intentional erosion of the tightly woven social fabric that once defined working-class England.

What really strikes me is how it goes beyond just the demographic changes, delving into the widespread sense of tension and alienation experienced by those of us who feel their sense of belonging and identity is being erased—not merely by the presence of foreign nations, but by the broader socio-political forces that allowed this transformation to take root.

The post is a stark reminder of the emotional and psychological toll that such sociological upheavals have on the people who once formed the backbone of these communities.